Pests are out in full force. Protect your crops this summer with the addition of an adjuvant that can double the potential of your insecticide. Using technology that reduces evaporation and keeps tank mix droplets on the target in a liquid state twice as long as a typical surfactant, OMRI listed Ampersand® adjuvant gets more of your tank mix to the leaf and keeps it there longer, giving your insecticide time to perform its function. Learn more at www.attuneag.com

Weed Control in Lettuce

Economical and successful weed control in lettuce can be accomplished by utilizing key cultural practices, cultivation technologies and herbicides. Planting configurations vary from 40-inch wide beds with two seedlines to 80-inch wide beds with 5 to 6 seedlines. Recent studies of weeding costs for lettuce ranged from $454 to $623/A for 80-inch wide beds with 5 seedlines of head and 6 seedlines of romaine hearts lettuces, respectively (see coststudies.ucdavis.edu/en/current/commodity/lettuce/).

Weeding costs included the following: Herbicide applied in 4-inch wide bands over the seedlines, cultivation, auto thinning using a fertilizer to kill unwanted lettuce plants and hand weeding/double removal. The costs for auto thinning also include fertilizer costs, which can satisfy the need for the first fertilizer application.

Significant weed control is accomplished by practices that occur before the crop is planted. For instance, weed pressure is affected by prior crop rotations and how much weed seed was produced in them. The weeding costs given above are rough averages. If weed pressure is light, weeding costs can be lower, but if weed pressure is high, weeding costs can be much higher. In the Salinas Valley, good management of weeds is possible with rotational crops such as baby vegetables (spinach, baby lettuce and spring mix) because they mature in 25 to 35 days and don’t allow weeds to set seed. Long-season crops such as pepper and annual artichokes allow multiple waves of weeds to germinate and which are difficult to see and remove once the plants get bigger.

Preirrigation is standard practice to prepare the beds for planting. It stimulates germination of a percentage of weed seeds in the seedbank, and they are subsequently killed by tillage operations. Studies have shown that preirrigation followed by tillage lowers weed pressure to the subsequent crop by about 50%. In organic production, pregermination is one of the most powerful practices for reducing weed pressure, and if time allows, it can be repeated to further reduce weed pressure.

Preemergence Herbicides

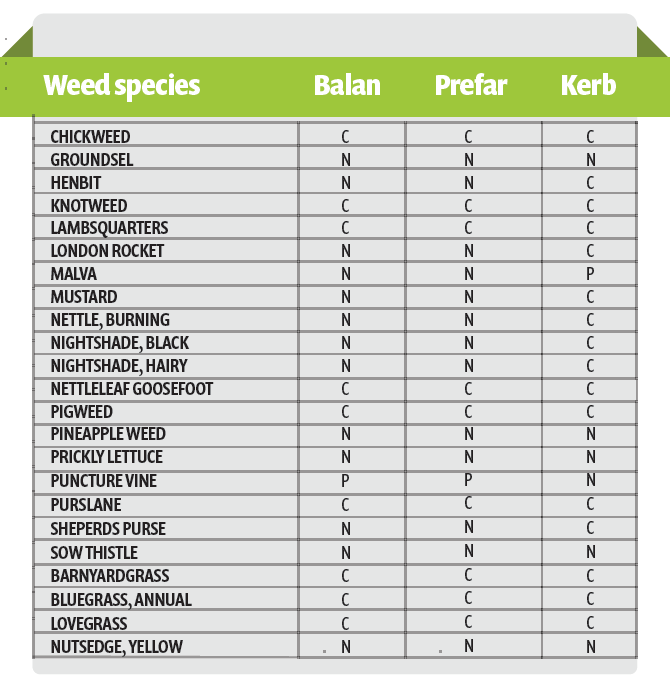

There are three pre-emergence herbicides available for use in lettuce production: Balan, Prefar and Kerb. Balan and Prefar provide good control of key warm season weeds such as lambsquarters, pigweed and purslane, as well as grasses (Table 1). Kerb is better at controlling mustard and nightshade family weeds such as shepherd’s purse and nightshades. Balan is mechanically incorporated into the soil and Prefar and Kerb are commonly applied at or post planting and incorporated into the soil with germination water.

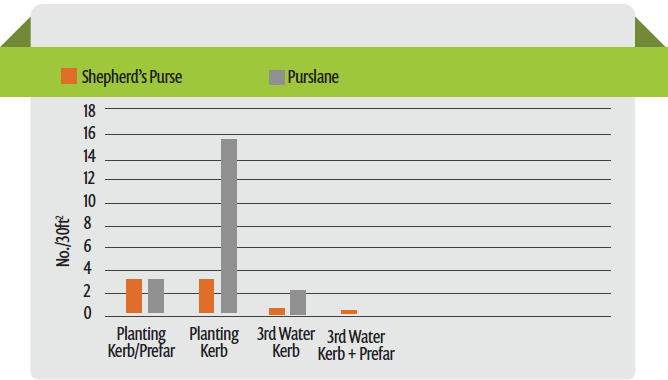

Kerb is more mobile in water than Prefar which can lead to issues with its efficacy. Often 1.5 to 2.0 inches of water are applied with the first irrigation to germinate the crop which can cause Kerb to move below the zone of germinating weed seeds, especially on sandy soils. For instance, Kerb is capable of controlling purslane however, its efficacy can be low on sandy soils due to its movement below the zone of germinating weed seeds with the first germination water. Prefar does not leach as readily as Kerb and that is why these two herbicides are often mixed in the summer to control purslane (Figure 1).

In the desert, the use of delayed applications of Kerb has been used for many years. Due to the large amounts of water that are applied to keep the seeds moist and cool, Kerb is applied in the 2nd or 3rd germination water, approximately 3 to 5 days following the first water, just prior to the emergence of the lettuce seedlings. The amount of water applied in the second and third irrigation is less than the first application and therefore does not push the Kerb as deep in the soil. Although the Salinas Valley is cooler than the desert, evaluations here have also found delayed applications to improve the efficacy of Kerb (Figure 2). These data illustrate the loss of control of purslane by Kerb when applied before the first germination water, as well as the improvement in efficacy that results when applied after the first germination water. It also illustrates the role that Prefar plays in the control of purslane when the efficacy of Kerb is reduced by being pushed too deep. Clearly, there is benefit from applying the Kerb in the 2nd or 3rd germination water because it helps to keep it in the zone where weed seeds are germinating.

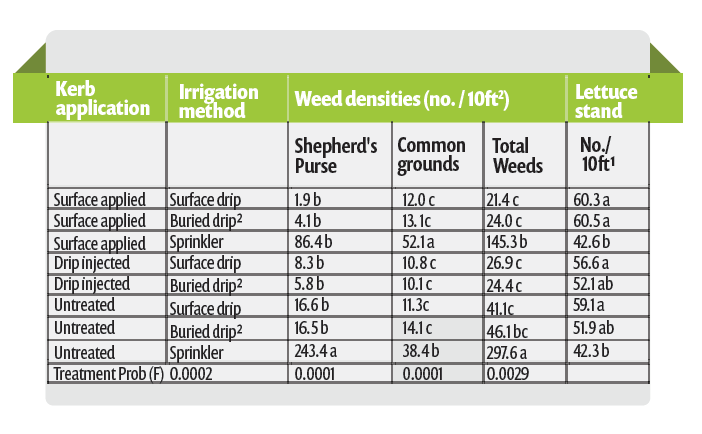

The use of single use drip tape injected 3 inches deep in the soil has become popular in the Salinas Valley. The uniformity of using new tape with each crop has allowed growers to consider using drip irrigation to germinate lettuce stands. Although the same amount of water may be applied to germinate the stand with drip irrigation as with sprinklers, the water tends to move upward with drip irrigation. In drip germinated lettuce, Kerb is sprayed on the soil surface and is solubilized by the upward movement of the drip applied water which allows it to move just deep enough in the soil to control germinating weeds, but not too deep to reduce its efficacy (Table 2). Interestingly, drip germination alone resulted in fewer weeds than sprinkler irrigation.

Lettuce is typically planted with 4-5 times more seed than is needed in order to assure a good stand. At about 3 weeks after the first irrigation, lettuce is thinned. Traditionally lettuce has been thinned by hand, but increasingly growers are using auto thinners which spray an herbicide (Shark) or concentrated liquid fertilizer (e.g. AN 20, 28-0-0-5, and others) to kill the unwanted plants and achieve the desired plant spacing. In the process of thinning by hand or by auto thinning, a significant portion of weeds in the seedline is also removed.

Automated Thinning and Weeding

About 10 to 14 days after thinning, hand weeding is carried out to remove weeds from the seedline and any double lettuce plants that were not removed in the thinning operation. An increasing number of Salinas Valley growers are using autoweeders prior to hand weeding. There are several autoweeders available: Robovator (Denmark), Steketee (Netherlands), Ferrari (Italy) and Garford (England). These machines use a camera to capture the image of the seedline and a computer that processes the image and activates a kill mechanism (a split or spinning blade) to remove unwanted plants. The machines were originally designed for use with transplanted vegetables. We tested auto weeders and found that they remove about 50% of the weeds in the seedline and reduced the subsequent hand weeding times by 35%. In order to safeguard the crop plants, the auto weeders leave an uncultivated safe zone around the crop plants where weeds can survive. As a result, auto weeders do not remove all the weeds in the seedline, but they help to make subsequent hand weeding operations more efficient and economical.

Depending on the weed pressure, some lettuce fields are hand weeded one more time a week or so prior to harvest. Given the practices just outlined, perennial weeds are not problems in the typical lettuce rotations in the Salinas Valley. The rapid turnaround of the crop (55 to 70 days during the summer) and the frequent use of cultivation does not allow enough time for weeds like field bind weed or yellow nutsedge to build up root reserves or nutlets before they are cultivated or disced out. In the summer, purslane is the biggest concern because it can build up high populations in the seedbank and, because of their fleshy tissue, can set seed even after being cut by the cultivator knives. As a result, if it is not effectively controlled in prior rotations, it can result in high hand weeding costs. Growers address purslane issues by making bedtop applications of the combination of Prefar and Kerb, as well as by a combination of other practices outlined above.

Although there have been no new herbicides registered for use on lettuce in many years, there have been significant technological developments that have improved efficiency of weed control in lettuce. The increasing use of single use drip tape and new automated thinning and weeding technology have recently contributed greatly in this regard.

Making Sense of Biostimulants for Improving your Soil

Biostimulants…bio what??? You may have heard or read this phrase several times over the past year as this product category gains traction in the agricultural marketplace. Confused about what exactly constitutes a biostimulant? You are not the only one! A biostimulant includes “diverse substances and microorganisms that enhance plant growth” or helps “amend the soil structure, function, or performance.” Got it? No? That is ok, please read on for more information.

Market Confusion

The exact definition of what a biostimulant is, and what it is not, can be confusing and leave some folks scratching their head on what to expect regarding product performance (See Figure 1). A biostimulant tends to be an “environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic products” and can have multiple impacts on the crop or soil, although the exact definition of the category is vague and open-ended. This uncertainty has received increased attention by regulators, and we should expect to see more precise definitions soon.

As it stands, there are many active ingredients in this arena, and some growers have struggled to find the right fit for their farm. This confusion is regrettable given the increasing popularity of the category and the forecasted sales growth rates. For example, the global market for biostimulants was valued at $2.19 billion in 2018 and is projected to have a compound annual growth rate of 12.5% from 2019 to 2024.

Matching Clear Goals

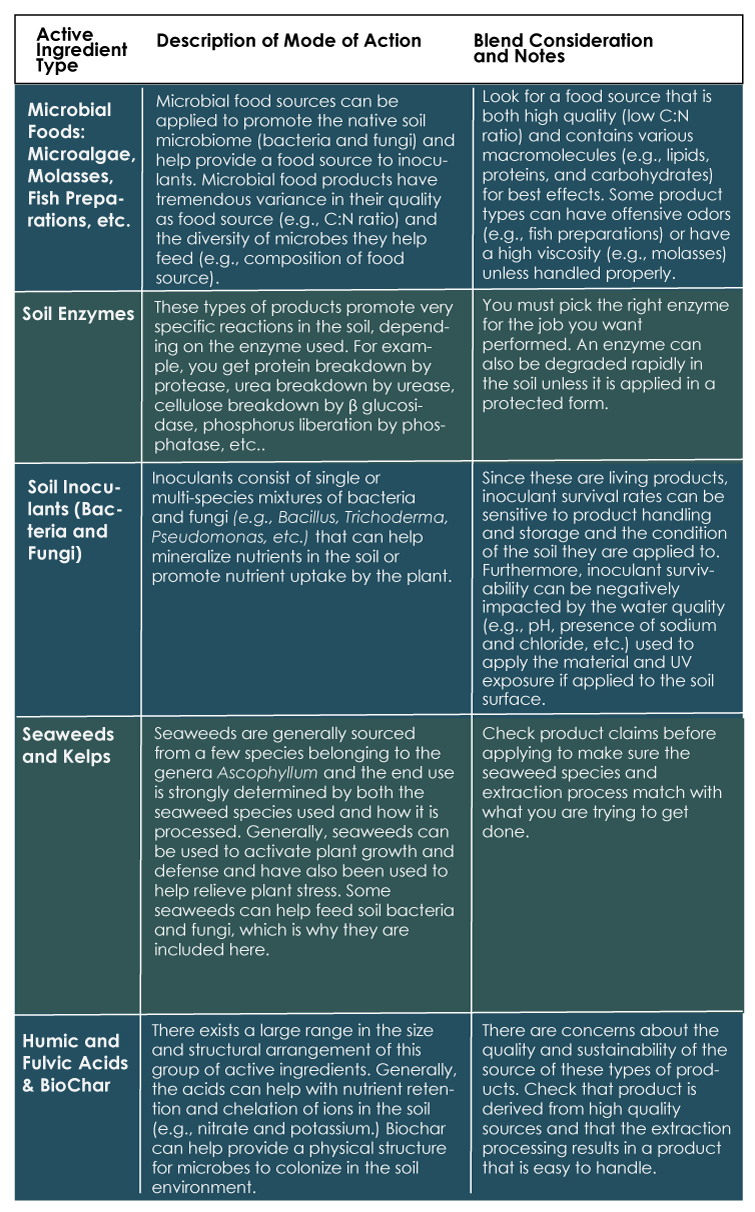

Biostimulants can be derived from a laundry list of different materials, with studies listing roughly eight major classes of active ingredients or more, each with unique properties and modes of action. However, my experience in the field suggests that many of us have unfortunately lumped the various products in this category into one large “other” bucket for simplicity, regardless of the difference in how the product works or what outcome should be expected.

Below I help clarify the role of several active ingredients to allow you to better understand and also mix and match the desired characteristics you are looking for (See Table 1). This reference table will allow you to determine which features you want to put to work into your biostimulant blend based on your crop production method, application equipment, and comfort level. The biostimulant categories listed complement an agronomically sound fertilizer and irrigation program and should be included as a part of a comprehensive crop management program. Caveat: I do not have enough space to list all possible modes of action, but instead I limit the table to the materials that have an impact on the soil.

Understanding the Nuances

The biostimulant category offers many exciting opportunities to growers and can deliver new functionality to common fertilizers when used in a blend. Before jumping into this ‘other’ category, start with the following question “What features am I looking for?” This honest query will help you pick the correct ingredient needed and bring clarity to the nuances of the biostimulant category. Getting your product blend right from the get-go can help improve the soil on your farm and help jumpstart your 2020 yield and quality goals. Please consult with your local sales representatives to help pick the right active ingredient for the job and be sure to jar test any new blend ideas you have prior to tank mixing for compatibility concerns.

Furthermore, running a pilot or test study can be a great way to learn which biostimulant product is right for your crop and production system. Keeping good records of your observations will help jog your memory about product performance as the season wears on and will help you formulate the right blend for the job. A good pilot or trial plan can go a long way with helping you keep track of important information on how your biostimulant blend is impacting your crop.

Hungry for more information about biostimulants and what they can do for you? Many trade publications, such as the one you are reading now, have begun to cover this category in more detail and there are several good articles out there that are worth reading. Below I provided some recommended reading to help get you started along with some online resources that are worth a look.

About the Author

Dr. Karl Wyant currently serves as the Director of Ag Science at Heliae® Agriculture where he oversees the internal and external PhycoTerra® trials, assists with building regenerative agriculture implementation, and oversees agronomy training. Prior to Heliae® Agriculture, Dr. Wyant worked as a field agronomist for a major ag retailer serving the California and Arizona growing regions. To learn more about the future of soil health and regenerative agriculture, you can follow his webinar and blog series at PhycoTerra.com.

Further Resources

- Soil Health Partnership Blog – https://www.soilhealthpartnership.org/shp-blog/

- Soil Health Institute Blog – https://soilhealthinstitute.org/resources/

- PhycoTerra® Blog – https://phycoterra.com/blog/

References

Albrecht, Ute. (2019). Plant biostimulants: definition and overview of categories and effects. IFAS Extension HS1330.

Calvo Velez, Pamela & Nelson, Louise & Kloepper, Joseph. (2014). Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant and Soil. 383. 10.1007/s11104-014-2131-8.

Drobek, Magdalena & Frąc, Magdalena & Cybulska, Justyna. (2019). Plant Biostimulants: Importance of the Quality and Yield of Horticultural Crops and the Improvement of Plant Tolerance to Abiotic Stress—A Review. Agronomy. 9. 335. 10.3390/agronomy9060335.

Rouphael, Y., Colla, G., eds. (2020). Biostimulants in Agriculture. Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA. doi: 10.3389/978-2-88963-558-0

Detection of Marked Lettuce and Tomato by an Intelligent Cultivator

Weeds are difficult to control in lettuce and tomato due to labor shortages, increasing costs of hand weeding and limited herbicide options. Lettuce is very sensitive to weed competition, plus there is no tolerance for contamination of bagged lettuce salad mixes with weeds; therefore, weeds must be controlled if lettuce is to be harvested.

Consequently, mechanical weed control is an important part of an integrated weed management program in conventional and organic vegetable crops. Traditional inter-row cultivation, however, only removes weeds between crop rows and leaves the weeds within the crop row. The removal of in-row weeds requires hand weeding, a time-consuming and expensive process.

Vegetable Weed Control Costs

Weed control costs for conventional head lettuce production in California are estimated at $216 to $319 per acre, while weed control costs in organic leaf lettuce are $489 per acre, on average, at current labor rates. In conventional processing tomatoes, weed control costs are about $225 per acre or 12% of production costs. Additionally, hand weeding costs have increased due to labor shortages, changes in California overtime regulations and increasing minimum wages as well as decreased labor immigration from Mexico. The result is greater vulnerability of growers to crop losses due to weeds.

Automation of weed removal may be a method to contain or reduce weed control costs in vegetable crops. Intelligent intra-row cultivators (IC) provide an alternate weed management option to standard inter-row cultivation. Previous results have shown that IC can reduce the need for hand weeding compared to standard cultivators and may reduce weed control costs.

The Robovator® cultivator evaluated by Lati et al. (2016) relied on pattern recognition of the rows and crop plants within the rows based on the expected crop spacing within the rows. When these spatial cues are unavailable, as can occur in an organic field with a high weed density, this approach cannot differentiate between crops and weeds, and thus it relies on a size difference between crops and weeds, as well as a low to moderate weed population to function accurately.

Intelligent Cultivation. Intelligent intra-row cultivation requires three technologies; a machine-vision system that detects crop plants and weeds, image classification and decision algorithm that differentiates between crop plants and weeds, and an automated weed removal mechanism that controls the weed while protecting the crop. Precision guidance systems, decision algorithms, and precision in-row weed control devices are commercially available or are at an advanced level of development. Accurate crop detection and differentiation from weeds, at normal cultivation speeds, would allow for greatly improved intra-row cultivators.

Weed/Crop Differentiation. The main challenge for intelligent intra-row cultivation is to differentiate between crops and weeds using digital imagery and processing at field operation speeds of at least 1 mph in high weed density fields with travel speeds above 2 mph required for economic acceptability for low to moderate weed loads.

A new method of crop and weed differentiation called “crop signaling” is presented in the research “Crop Signaling for Automated Weed/Crop Differentiation and Mechanized Weed Control in Vegetable Crops” by Raja et al. 2019 out of UC Davis. It is based on the idea that the identity of the crop is known with certainty when it is planted, whether transplanted or seeded. Thus, if the crop has a marker or signal that an IC can reliably detect, then the IC would recognize the signal and protect the crop. Plants without the signal, i.e., weeds, would not be protected and would be removed by the IC. The objective of this work was to test a crop signaling system for crop detection accuracy and weed control efficacy by an IC in lettuce and tomato.

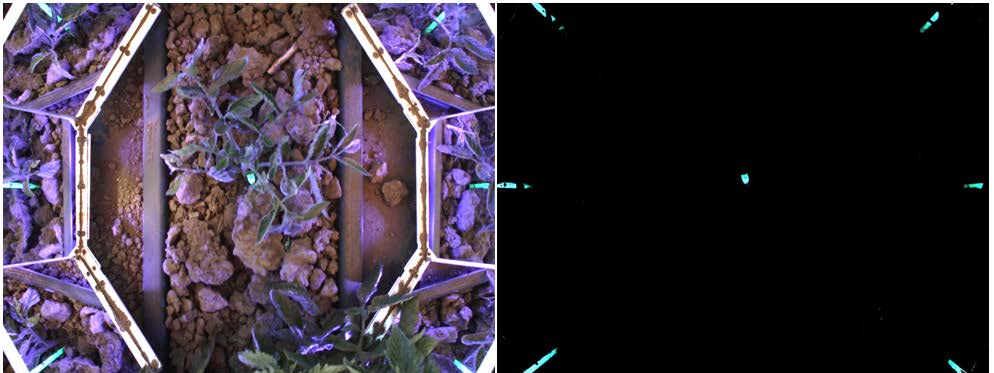

Marking System Descriptions. Two methods of plant signaling were tested, physical plant markers and topical markers. Biodegradable straws coated with a fluorescent marker were used as the plant markers in this study (Figure 1). The straws were then placed next to tomato seedlings in the planting trays and then transplanted together (Figure 2).

The topical marker used on plant foliage was green or orange fluorescent water-based paint (Figure 3a,b). A paint sprayer was used to apply the topical marker to lettuce foliage and tomato seedlings prior to planting, while they were in trays. Another method was to spray the marker onto tomato stems as they were transplanted (Figure 4).

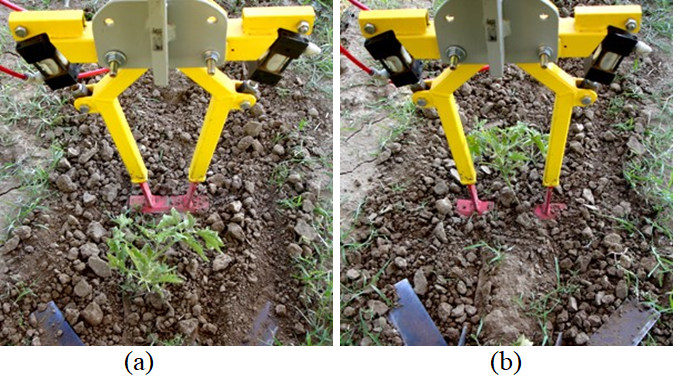

Intelligent Cultivator. The IC used in this research was developed at the University of California, Davis. It uses a machine vision system specifically designed to detect the physical labels and topical markers on the crop (Figures 5&6). Weed control was done by mechanical knives, which the IC opens (Figure 6b) to avoid the marked crop plants and closes (Figure 6a) to uproot weeds in the intra-row space.

Field Trials

Eight field trials in tomato at Davis, Calif., and six in lettuce at Salinas, Calif., were conducted during 2016-2018.

Tomato. Field trials in processing tomatoes were located on a silt loam soil on the UC Davis vegetable field crops research station near Davis. The tomatoes were seeded in trays and kept in a greenhouse for 45 to 60 days until they were about 10 inches tall. Tomatoes were transplanted into 60-inch beds at 15-inch spacing in a single center row. Two tomato trials were carried to yield. Plant labels were added to seedling trays prior to transplanting (Figure 1) or the topical marker was applied to trays of tomato seedlings as described above (Figure 4). Tomato transplants were marked with paint 4 inches above the soil line. About three weeks after planting, all plots were cultivated with a standard mechanical cultivator which only removed weeds outside the plant line. The standard cultivator left a 7-inch non-cultivated band centered on the crop row.

Weed densities by species were measured before and after cultivation in four 7-inch-wide (centered on crop row) by 20-foot-long sample areas randomly placed along the length of the plots. The time required by a laborer to hand weed the 20-foot areas was recorded. Two tomato trials were maintained until harvest so that marketable yield data could be collected.

Lettuce. Field trials using Romaine lettuce were conducted in a sandy loam soil at the USDA research station in Salinas, Calif. Four weeks after seeding, the whole experiment was cultivated with a standard mechanical cultivator. The standard cultivator left a 6-inch non-cultivated band centered on the crop row (Figure 7). The IC operated within .75 inches of the lettuce plants on all sides. Pre-cultivation weed counts were measured the day before cultivation and post-cultivation weed counts were taken the day after cultivation. Weed densities were measured in a 6-inch band centered on the crop row in each of two 20 -foot-long samples in the field. Weeds that were uprooted were considered dead. After cultivation, hand weeding was performed and timed as described for the tomato trials. The time spent by a laborer to hand weed with a hoe was recorded.

The 2017 lettuce trials were maintained until commercial maturity and number of marketable heads and weight of marketable heads were recorded. The 2018 trial was conducted at a commercial lettuce field near Salinas, Calif.

Statistical Analysis. RStudio Version 1.1.383 was used for statistical analysis. Differences between pre- and post-cultivation weed counts determined weed removal effectiveness. The most efficacious treatments removed the greatest proportion of weeds.

The difference in weed densities between pre and post cultivation were analyzed using analysis of co-variance, to measure the effect of cultivator type on weed density. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the hand-weeding time data to measure the effect of the cultivators. Weights were determined for both lettuce and tomato yields, and in lettuce, the number of heads was also determined.

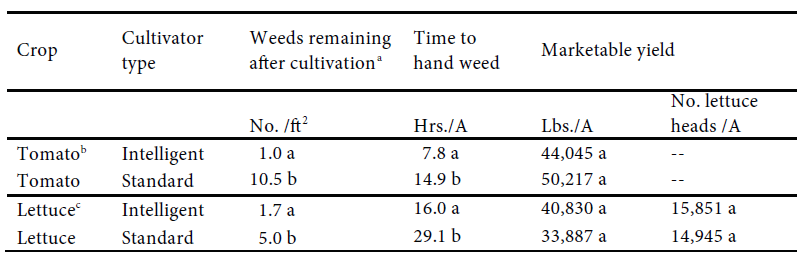

Weed Control. The IC was more effective than the standard cultivator at removing weeds from the inter-row space. The data were pooled separately for tomato and lettuce. In tomato seed lines, 1 weed per square foot remained after IC while 10.5 weeds per square foot remained after standard cultivation. This is a 90% reduction in the number of weeds remaining after cultivation (P<0.05). In the lettuce trials, 1.7 weeds per square foot remained in the seed line after intelligent cultivation while 5 weeds per square foot remained after standard cultivation, which is a 66% reduction in weeds remaining after cultivation (see Table 1).

Handweeding in the tomato trials required 7.8 hours/A following the IC while the standard cultivator required 14.9 hours/A which is a 48% reduction (P<0.05). Hand weeding of lettuce required 16 hours/A following cultivation the IC while 29 hours/A was required for the standard cultivator, a 45% reduction in time (P<0.05).

The time-spent hand weeding after IC cultivation was a notably smaller percentage reduction than it was for weed densities, i.e. 48% vs. 90% in tomato. This is because the IC consistently removes the readily accessible weeds that are more than an inch from the crop; while the remaining weeds after IC cultivation are typically close to the crop plants and take more time for the field crew to remove than weeds further from the crop plant. The IC did not remove all the weeds it passed over due to some algorithmic uncertainty in the precise location of the crop’s main root and a risk-averse control strategy. Thus, weed control in close proximity to crop plants may still require some hand weeding. However, significant reductions in manual labor were achieved while maintaining effective weed control.

Crop Yields. There was no difference between the cultivators in their effect on tomato fruit yield in 2017 (P>0.05) (Table 1). The 2018 tomato yields had marketable fruit yields in the IC and standard cultivator treatments of 44,045 and 50,217 lbs./A, respectively (P>0.05). Similarly, there were no differences between the cultivators in their effect on lettuce yields (P>0.05) (Table 1). Yield data were analyzed both as the number of marketable lettuce heads per acre and fresh weights.

Weed/Crop Differentiation. One of the biggest challenges for automated intra-row cultivation is to enable a computer and vision system to differentiate between crops and weeds at normal field travel speeds. The commercially available IC ‘Robovator®’ uses pattern recognition to recognize the crop row and can perform intra-row weeding at speeds of 1 mph (Lati et al. 2016). However, this requires a distinct crop pattern best found such as in a transplanted field where the crop is much larger than the weeds and the crop stand is consistent. Further, when high weed densities obscure the 2-dimensional crop row pattern, the intra-row weeding program does not work.

Two types of crop signals were tested, physical plant labels and topical markers. The methods have very low false positive error rates and the classification accuracy achieved for both techniques approaches 100%. The crop signaling technique appears to be effective in creating a reliable method for automatic detection of crop plants in vegetable fields with high weed densities. Crop signaling technology could facilitate development of automated weed control robots that are as accurate in crop/weed differentiation as human workers are.

A recommendation for future work is to develop a commercially viable marking method that is machine readable, yet does not contaminate harvested produce or the field soil and subsequent rotational crops. For transplanted stem crops like tomato, a biodegradable machine-readable tag attached to each stem as the transplanter sets the plants should be explored for commercial potential. Lettuce will probably require a machine-readable label attached to the first true leaves or a machine-readable label on the fiber-coated plant plug as it is set in the soil as is done with the Plant Tape® (www.planttape.com) system of vegetable transplanting.

Regardless of the technology used for crop weed differentiation, development of intelligent weed removal technology has improved weed control programs for horticultural crops that continue to rely on a limited number of herbicides and hand weeding. However, there is much more to do to improve vegetable weed control.

Acknowledgments. Thanks to the USDA Institute of Food and Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative (USDA-NIFA-SCRI-004530) the California Tomato Research Institute and the California Leafy Greens Research Program for financial support.

References

Lati, R.N., M.C. Siemens, J.S. Rachuy, and S.A. Fennimore. 2016. Intra-row Weed Removal in Broccoli and Transplanted Lettuce with an Intelligent Cultivator. Weed Technology 30:655-663

Raja R, Slaughter DC, Fennimore SA, Nguyen TT, Vuong V, Sinha N, Tourte L, Smith RF, Siemens MC (2019) Crop signaling: a novel crop recognition technique for robotic weed control. Biosystems Engineering 187:278-291.

Virus Pathogens: Challenges to the Health of Vegetable Crops

Farmers and other field professionals producing vegetable crops face a bewildering array of challenges. Insects and mites feed on, disfigure, and eat away at produce quality. Weeds compete with the vegetables for precious resources and can require extensive labor to be removed. Fertilizer and water inputs can be costly. The economic cycle of planting, growing, harvesting, and marketing can be a “black hole” that engulfs company resources while offering few guarantees of profits. Another group of challenges is embodied by the many plant pathogens that cause diseases of vegetable crops. One particular group of pathogens of interest are the viruses that infect plants.

Virus Pathogens of Plants

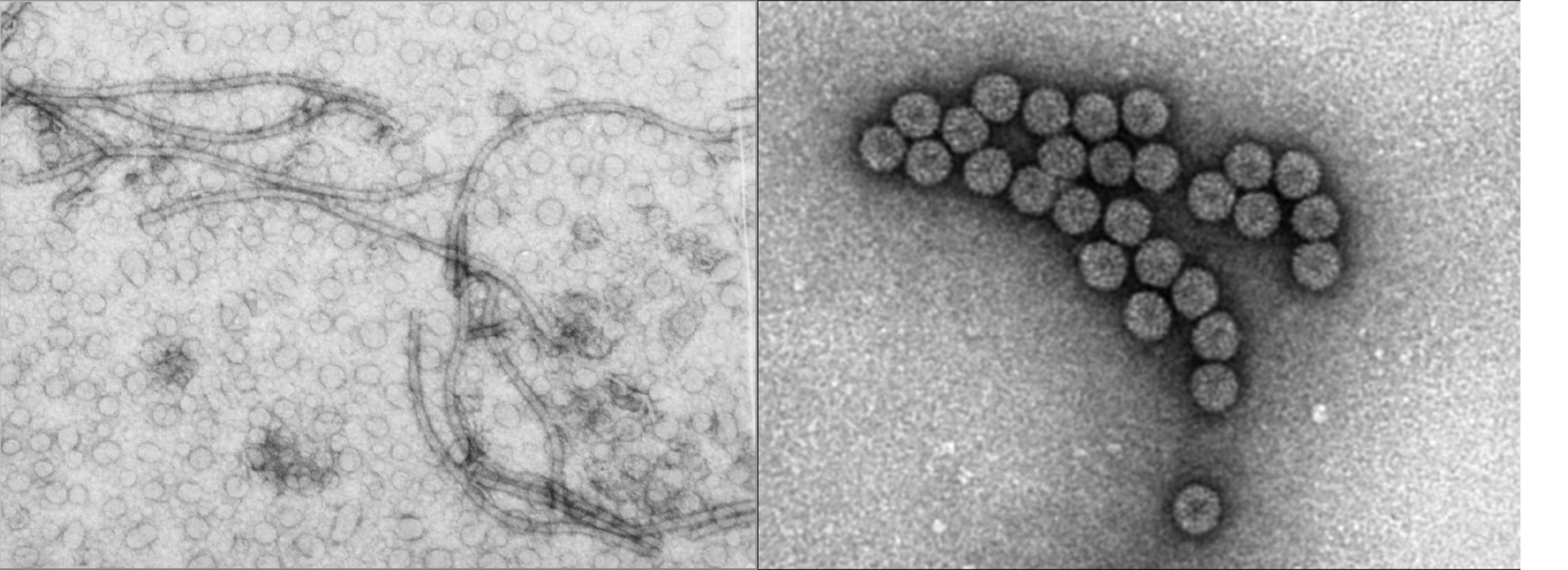

Viruses that infect plants are similar, in shape and constitution, to the viruses that infect insects, animals, and yes, people. A virus consists of a piece or two of genetic material (either DNA or RNA) that is surrounded and protected by a protein coat or covering. In the grand scheme of biology, such a nucleic acid + protein structure is extremely simple and basic. This entity is also extremely tiny. Since a virus is composed of two types of chemicals, it is much smaller than a plant cell and cannot be observed with a regular microscope. Only with the use of electron microscopes can the body of the virus be observed. The outer protein coat gives the virus a distinctive shape, and plant viruses can look like long flexible threads, short rigid rods, or spherical, geometric polyhedrals.

Plant viruses, like all viruses, do not function or operate outside of their hosts. To become active the virus must be introduced into a living plant cell, after which the virus mechanism activates and highjacks the cell’s processes, forcing the host cell to produce more virus RNA or DNA and virus proteins. These components are assembled into new viruses which are then translocated throughout the plant by being carried in plant fluids that stream into stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits.

Diseases Caused by Viruses

As with viruses that infect people and animals, plant pathogenic viruses at first show no evidence of their initial incursion into the host. There is a latent period or lag-time during which the virus is steadily orchestrating the manufacture of additional virus nucleic acids and proteins. At a certain critical point, the virus population causes enough physiological and metabolic disruption so as to cause visible symptoms, which collectively we call the disease.

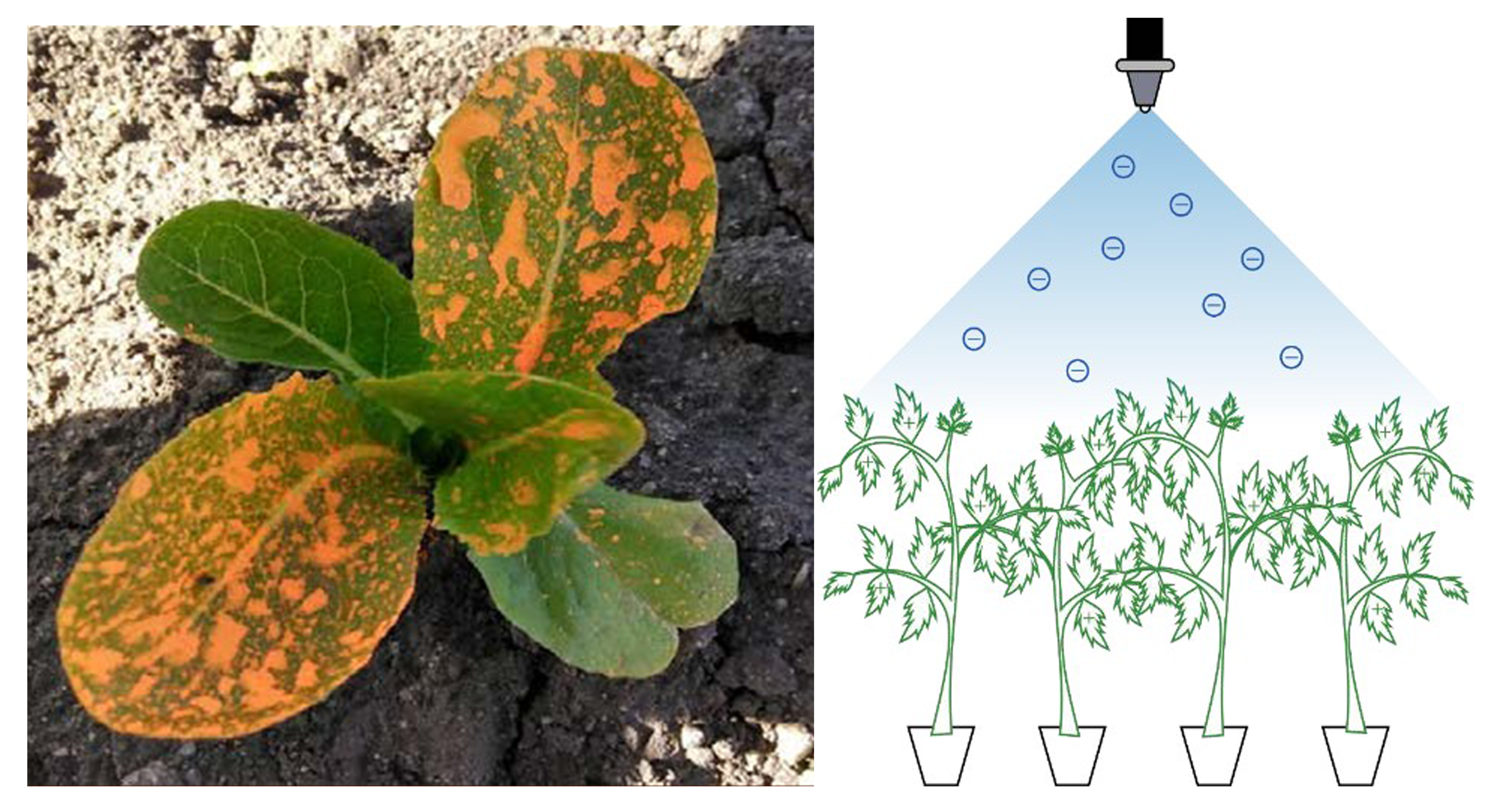

Disease symptoms caused by viruses can vary greatly and are influenced by the vegetable variety, age of plant when first infected, the strain of the virus, and environmental conditions under which the crop is grown. In general, vegetable crops infected with viruses will show one or more types of foliar symptoms. Leaf color changes with the development of yellow or brown spots, light and dark green patterns (mosaic, mottling), concentric ring patterns (ringspot), and yellow or white blotches and streaks. In some cases, the entire foliage of the plant turns yellow, orange, or red. Some viruses cause a curious reaction where only the veins of the leaf become yellow or brown. Leaves can be misshapen in various ways, from simple curling, to unusual elongation (strap leaf), to severe twisting and deformation. Internodes along the stem become abnormally shortened, resulting in tight bunching of leaves. Flowers also change appearance with streaks of color in the petals (color break). For fruiting vegetables, the fruit may show only subtle color breaks and patterns, or alternatively become grossly deformed. Overall plant growth can be stunted and crop development can be delayed.

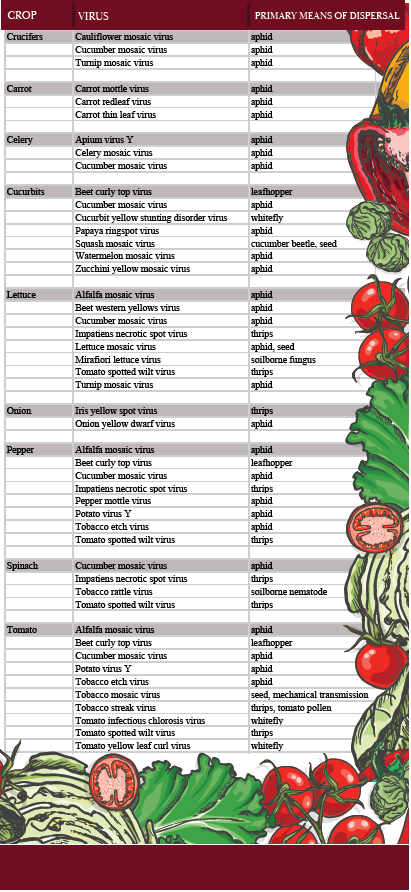

All vegetable crops suffer from at least one virus pathogen, while some crops are subject to a dozen different ones. Table 1 lists selected vegetable crops and some of the viruses affecting these crops in the U.S. Like fungal and bacterial pathogens, virus pathogen occurrence and importance vary with geographic region. A virus that is important on California lettuce may be incidental or lacking on lettuce in Florida. Likewise, the set of viruses that North American tomato growers must deal with will be different than tomato viruses occurring in South America or Asia.

The economic impact of a particular crop-virus interaction depends on the inherent aggressiveness of the virus, incidence of the disease, and the susceptibility of the crop. Regarding the crop, a critically important factor is the type of harvested commodity. For example, leafy commodities such as lettuce and spinach will be especially vulnerable to viruses that cause leaf symptoms. The viruses of pepper that cause fruit malformations are more important than the pepper viruses that only cause mild mosaics in the foliage. For celery grown in California, cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) causes some leaf mosaic and mottling but rarely causes any symptoms on the celery petioles and, therefore, is of little concern. However, a different virus, Apium Virus Y, can cause celery petioles to turn brown, making the celery unmarketable.

Detecting and Diagnosing Viruses

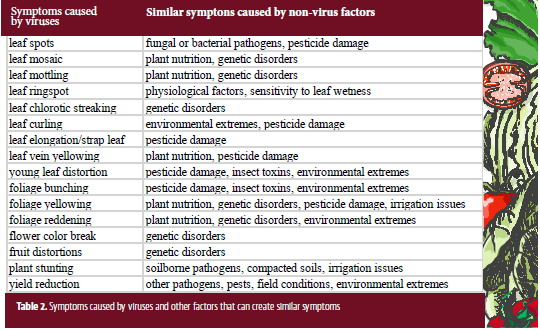

Confirmation of a virus requires testing. We acknowledge that experienced growers and field personnel, who have looked at virus diseases of a particular crop for many years, can develop a good diagnostic sense for such problems. However, to be scientifically sound and accurate, diagnosing virus diseases cannot be achieved without clinical testing. Virus disease symptoms pose particular challenges to diagnosticians because the wide range of virus-like symptoms can also be caused by other factors.

Symptoms caused by viruses can also be caused by genetic disorders, nutritional imbalances, environmental extremes, phytotoxicity from pesticides and fertilizers, and other factors (see Table 2.) Fortunately, diagnostic labs have the tools that can identify most of the commonly occurring viruses in vegetables. Such tests rely on either serology (using antibodies that detect the antigens of virus proteins) or molecular biology (using probes that recognize nucleic acid sequences of the virus.)

Epidemiology of Virus Diseases

Development of virus diseases of plants involves several factors. In contrast to some human viruses, plant viruses are not moved around in the air or deposited on surfaces waiting to come into contact with a plant. Rather, plant pathogenic viruses typically originate from a living source or “reservoir.” (Factor 1) The reservoir is often an infected weed that is near the site where the vegetable crop will be planted, or the reservoir can be an infected volunteer crop plant in the field. Vectors (Factor 2) are the insects, mites, and nematodes that have fed on a virus-infected plant, ingested virus particles, and now are capable of injecting the viruses into the next plant that is fed upon. For the great majority of viruses that infect vegetables, the viruses are moved by vectors from reservoir hosts to healthy crops (Factor 3). Aphids are the most common vectors (See Table 1.) Other insects (thrips, leafhoppers, beetles) also carry viruses, as do a few soilborne nematodes and one soilborne fungus.

The epidemiology, or progress of disease spread, depends on the complex interaction of the three factors mentioned above.

Factor 1 Reservoir: What is the nature of the virus reservoir? Which weed species are present? Are there high numbers of virus-infected weeds or volunteer plants in the area? A virus with a broad host range, such as Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), may be present in dozens of weeds and numerous volunteer plants on a particular ranch.

Factor 2 Vector: Which vectors are in the vicinity? What are their populations and dispersal patterns? How do wind patterns and geographic features influence dispersal? What is the extent of vector increase within the crop, which can result in plant-to-plant spread within that planting?

Factor 3 Vegetable Crop: What is the crop diversity in the area being considered and which viruses affect these crops? For example, could CMV, which has a broad host range, spread between different vegetables? If the region is widely planted to one crop, such as lettuce, will a particular virus affect many lettuce plantings? Too much of the same crop, densely cropped in one region, could result in rapid virus spread and disease epidemics. In contrast, if a region has only one onion field among many non-allium crops, a narrow host-range pathogen such as Iris yellow spot virus will infect only the onions. The answers to these and other questions have significant bearing on the management of virus diseases.

Managing Virus Diseases

Diagnosis: The first step in disease management is accurately identifying the precise pathogen involved. Molecular and serological assays are available for most of the major virus pathogens affecting vegetables. Knowing which virus is involved enables one to know the reservoir plants harboring the virus, the vectors involved, and the potential target crops.

Exclusion: Prevent the virus from entering the production system. For lettuce, cucurbits and tomato, some viruses are carried in the seed; therefore, use seed that has been tested or certified to not harbor the pathogen. For crops started as transplants, employ IPM practices to prevent infection at the transplant stage. Note that for the few vegetable crops propagated by cuttings or plant divisions (example: artichoke), viruses will be readily spread if infected propagative material is used to plant new fields.

Reservoir host eradication: Remove the initial sources of the virus, which are infected weeds and volunteer crop plants. Plant viruses are present mostly in living plants and generally not in soil, water, equipment surfaces, or the air. Controlling weeds and other reservoir plants is therefore a critical part of virus control.

Manage the vectors: Use IPM practices to control the virus vectors. The great majority of vegetable-infecting viruses only reach a crop via an insect vector. Complete control of an insect pest is rarely possible, so strategies should attempt to manage the insects as best as possible. Keep in mind that the vectors are also present on the reservoir weeds and plants outside of the field. Once a virus is introduced into the crop, intra-field, plant-to-plant spread will be achieved only through movement of the vector.

Destruction of the old crop: Once a crop has been harvested, the passed-over plants and shoots growing from remaining crop roots can serve as virus reservoirs if they are infected. Old vegetable fields should, therefore, be disked and plowed under in a timely manner.

Resistant cultivars: If available, growers should select cultivars that are bred to be resistant to the virus pathogens. Note, however, that the usefulness of such genetic plant resistance may not last. Researchers found that the use of tomato and pepper cultivars resistant to TSWV has allowed for the development of “resistance breaking” (RB) strains of the virus. Through mutation and selection, these new strains of TSWV can cause disease in the previously resistant cultivars.

Chemicals or pesticides: Currently there are no chemical treatments that can be applied to plants that would prevent infection from viruses or prevent development of virus disease.

Cover Crops in California Agriculture: An Overview of Current Research

Growers throughout the country and around the world plant a wide range of cover crops for a variety of reasons. Cover crops can reduce soil compaction, improve water infiltration, improve soil structure, and feed soil microbes: they encourage a healthier and more diverse soil ecosystem.

Researchers in California are analyzing the best ways to incorporate cover cropping into the state’s diverse agricultural systems, from high-value vegetable production on the central coast to the cotton, tomato, and almond fields of the central valley.

Cover Crops on the Central Coast

Researchers working with central coast vegetable growers have devised innovative ways to use cover crops to reduce nitrate leaching and agricultural runoff, thereby improving both local ecosystems and soil health.

Eric Brennan and his team at the USDA Agricultural Research Service started the Salinas Organic Cropping Systems trial in the Salinas Valley in 2003 to understand the long-term impacts of various cropping systems and soil amendments. This trial focuses on organic lettuce and broccoli, two of the high-value crops grown in the area known as the nation’s salad bowl.

To maintain soil organic matter and provide nutrients to their crops, organic vegetable growers in this area prefer applying compost instead of planting cover crops. The amount of time that cover crops require for incorporation and decomposition can shorten the growing season for these high-value crops (Brennan & Boyd, 2012.) To make this practice more feasible for growers in the area, this group of researchers has developed three strategies for integrating cover crops into the vegetable cropping systems of the Central Coast.

Option 1: Plant the cover crops only in furrow bottoms, not the entire field. After 50 to 60 days of growth, the grower can spray the cover crops and then do the usual tillage necessary to prepare the ground for planting the cash crops. By planting time, the cover crop residue has already decomposed. This method reduces runoff and erosion but does not reduce nitrate leaching, so this is best for fields with runoff problems but without high nitrate levels. However, this method makes controlling weeds during a wet winter difficult and costs more than simply leaving the field bare (Brennan, 2017.)

Option 2: Plant non-legume cover crops on the vegetable beds and mow the cover crops repeatedly throughout the growing season. This maximizes nitrate scavenging while minimizing the amount of residue that needs to decompose right before planting. The ideal cover crop for this practice would be a grass, like cereal rye. Repeated mowing would reduce the amount of water lost to evapotranspiration from the cover crop but still enable the rye to scavenge nutrients that could otherwise be lost to leaching (Brennan, 2017.)

Option 3: Turn the cover crop residues into a highly nutritious juice and compost. To do this practice, a grower would plant a non-leguminous cover crop in October and allow it to grow until mid-December, at which point it will have scavenged most of the nitrogen that it will use. The grower then harvests the cover crop, leaving as little residue behind as possible. They can then feed the residue into a screw press, which will separate the liquids and solids. The liquid component has a relatively low nitrogen concentration and can be applied to the vegetable crop to fulfill some of the crop’s nutrient needs. The solid residues can be composted and applied at a convenient time, to provide organic matter to the soil (Brennan, 2017.)

Researchers are still working on refining these strategies, but they could allow central coast vegetable growers to reap the rewards associated with cover crops while maintaining a profitable enterprise.

Annual Systems in the Central Valley

For the past 20 years, Jeff Mitchell and his team at UC Cooperative Extension have studied the effects of reduced tillage and cover crops on a tomato-cotton rotation at the UC’s West Side Research and Extension Center. This study measures the efficacy of these practices in reducing air pollution and increasing soil organic matter. Reduced tillage and cover cropping have resulted in less dust emissions compared to conventionally managed fields (Mitchell et al., 2017.) They found that cover cropping increased soil organic matter more than conservation tillage alone did (Veenstra et al., 2006.) Overall, these practices have improved soil health by increasing aggregate stability, water infiltration, and soil organic matter while maintaining similar yields to the conventional system (Mitchell et al., 2017.) This study has allowed researchers to see the long-term effects of conservation tillage and cover cropping on tomato and cotton systems in the San Joaquin Valley.

Another UC research team in the Central Valley, led by Kate Scow at the Russell Ranch near UC Davis, examined the long-term effects of cover cropping on organic tomatoes and corn. These researchers found that cover cropping encouraged the proliferation of diverse types of beneficial fungi known as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Bender & Bowles, 2018). Under optimal environmental conditions, cover cropping was correlated with higher tomato yields. In contrast, corn did not enjoy the same benefits from organic management that the tomatoes did and had lower yields compared to fields without cover crops (Bender & Bowles, 2018). These studies have found important benefits to including cover crops in annual systems, but growers will need to further refine the practice to fit their needs.

Perennial Systems in the Central Valley

Amélie Gaudin and her team from UC Davis and UC Cooperative Extension are quantifying and communicating the benefits and tradeoffs of planting winter cover crops in almond orchards. They established trials throughout the Central Valley. Planting cover crops in almonds increases bee forage, improves soil health, and encourages resiliency. The researchers have found that cover crops resulted in increased water infiltration. Despite the common concern that cover crops would increase frost risk, they found that cover cropping did not affect ambient air temperatures 3 and 5 feet above the ground. Moreover, the ground cover worked as a buffer, keeping temperatures more stable than bare ground did (Gaudin, 2020.)

Other benefits included a decrease in sodicity, improved trafficability in the wintertime, and an increase in aggregation. The soil microbial ecosystem showed increased biomass. Bees enjoyed a more diverse, varied diet, contributing to better bee health. Finally, cover crops reduced weed diversity and growth. They did not reduce germination since both the cover crops and the weeds emerged at the same time. All these benefits start to outweigh the costs of implementation after about 10 years (Gaudin, 2020). Many of these soil and ecosystem benefits are not unique to almond orchards, and could also benefit other perennial cropping systems in the Central Valley.

Funding Options

UC and USDA researchers have found benefits to cover cropping in diverse agricultural systems throughout California, from almond orchards to lettuce and tomato fields. These include reducing erosion, compaction, and nutrient leaching, along with improving soil aggregation and providing habitat for beneficial insects. Cover crops may improve the soils upon which your crops depend and increase your operation’s resiliency in the face of a changing climate.

The California Department of Food and Agriculture’s Healthy Soils Program and the USDA NRCS EQIP provide incentives for planting cover crops. Check out cdfa.ca.gov/oefi/healthysoils/IncentivesProgram to learn more about the CDFA’s program. There are 10 technical assistance providers working throughout the state who can help you select your cover crop species, apply for the program, and implement your practices. Go to ciwr.ucanr.edu/Programs/ClimateSmartAg to find your closest climate smart specialist.

Works Cited

(2010). [Field day at West Side Research and Extension Center] [Photograph]. California Agriculture. http://calag.ucanr.edu/Archive/?article=ca.v070n02p53

Bender, S.F & Bowles, T.M. (2018). Effects of AMF diversity and community composition on nutrient cycling as shaped by long-term agricultural management. Russell Ranch 2018 Annual Report. https://asi.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk5751/files/inline-files/RRSAF%20Progress%20Report_2018.pdf

Brennan, E. B. (2017). Can we grow organic or conventional vegetables sustainably without cover crops? HortTechnology, 27(2), 151-161.

Brennan, E. B., & Boyd, N. S. (2012). Winter cover crop seeding rate and variety affects during eight years of organic vegetables: I. Cover crop biomass production. Agronomy Journal, 104(3), 684-698.

Gaudin, A. (2020, February 4). What do cover crops have to offer? [PowerPoint slides]. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. https://ucanr.edu/sites/calasa/files/319850.pdf

Mitchell, J. P., Shrestha, A., Mathesius, K., Scow, K. M., Southard, R. J., Haney, R. L., … & Horwath, W. R. (2017). Cover cropping and no-tillage improve soil health in an arid irrigated cropping system in California’s San Joaquin Valley, USA. Soil and Tillage Research, 165, 325-335.

Veenstra, J., Horwath, W., Mitchell, J., & Munk, D. (2006). Conservation tillage and cover cropping influence soil properties in San Joaquin Valley cotton-tomato crop. California Agriculture, 60(3), 146-153.