I will never forget my introduction to the miracle of agriculture in California’s Central Valley. I interviewed for an agronomist position for Netafim Irrigation in Fresno in June 1995. I was finishing my USDA post-doctoral job at the University of Lincoln, Nebraska and was tired of researching corn and soybeans. After my interview, they suggested I take my rental car on a tour around the Valley. I first drove to the Westside and was amazed at the variety of crops being grown, such as cotton, melons, alfalfa, fruit and nut trees, tomatoes, winegrapes and many others I didn’t recognize. After lunch, I looked to the east and was drawn to the snow-covered Sierras. I drove up highway 168 to Shaver Lake, the source of irrigation water for many of the crops I saw earlier in the day. I couldn’t believe that someone would pay me to live and work in an agronomist’s dream world. I accepted Netafim’s offer without hesitation.

Now that I have decided to retire, I am looking back at how California agriculture has changed from my first visit, and I wonder what lies ahead.

Start of the Journey

My career has allowed me to travel to growers’ fields throughout California and the Western U.S. When I started work in 1995, cotton and alfalfa were being grown on 3.3 million acres with only 400,000 acres of almond, 650,000 acres of grape and 60,000 acres of pistachio. Almond yields averaged around 1,000 lb/acre and growers were grossing around $2,000/acre. Citrus acreage was dominated by oranges with only 8,000 acres of mandarins. Sweet cherries were mainly grown in northern California with a few orchards in Tulare County. Processing tomatoes were grown on over 300,000 acres, and average yields were around 33 tons/acre. There were no blueberries being grown in California. Winegrapes were all grown on AxR 1 rootstock and growers were pulling out vineyards infested with phylloxera and replanting with new, less susceptible rootstocks. Winegrape growers invested in drip irrigation systems when they replanted their vineyards. Most growers fertilized with nitrogen once or twice a season and little else. Crops were irrigated by flooding or sprinklers. A few growers were experimenting with using drip irrigation in orchards and were deciding if they could get by with just a single drip line or would require two lines. Some growers were experimenting with buried drip irrigation in field crops. Buried drip asparagus was an early success in Firebaugh. Finally, the CCA program was just getting started with only a few hundred in California.

I became a CCA in 2003 soon after I became the Central Valley division agronomist for Western Farm Service. The exams were in-person and given four times a year in a few locations. The CCA program was challenged by attracting new members. With most consultants obtaining their PCA license and taking tests to qualify for different pest and disease categories, studying for a new program focused on agronomy and plant health was daunting. However, advisors that spent the time to obtain a CCA certification added to their skillset and knowledge of the multiple crops grown in California.

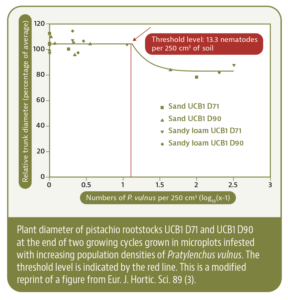

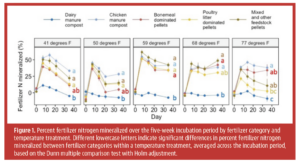

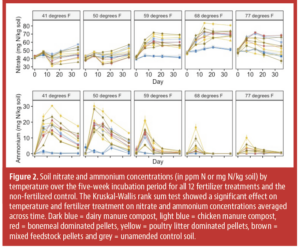

Nearly 30 years later, California agriculture has changed significantly. California crops are still highly diversified, and production values outrank the next largest state by an order of magnitude. Permanent crops now dominate the landscape, especially tree nuts like almond and pistachio, which respectively now cover 1.3 million acres and 460,000 bearing acres. Almond yields are more than double what they were in 1995, and many growers feel they must achieve 3,000 lb/acre yields to remain profitable. Cotton, now predominantly Pima, is grown on approximately 166,000 acres. Alfalfa grows on 500,000 acres, about half of the acres in 1995. Mandarin acres are 10 times what they were in 1995. Sweet cherries are now found in Kern County to capture the early market, and the Bing variety is being replaced by newer, earlier harvested varieties. Nearly all processing tomatoes are grown with buried drip irrigation and yields have more than doubled. There currently are over 7,000 acres of blueberries grown in California. The number of winegrape rootstocks are bewildering. Asparagus is being grown by one or two producers with acreage so low it is not reported. Drip irrigation predominates over nearly every acre of crops produced. Most growers are split applying liquid fertilizers through their drip systems. Fertilizer programs are based on balanced blends containing nearly all plant-essential nutrients, both macro and micro. Many growers claim to be applying much less nitrogen fertilizer and getting much higher yields than they did in the past due to the efficiency of application of microirrigation.

In 2012, The Harter Report was published at the request of the California legislature. The report performed a mass balance accounting of nitrogen in two watersheds that were vulnerable to nitrate pollution of groundwater, the Salinas Valley and Tulare Lake Basin. The report determined nitrogen fertilizer was being overapplied and unaccounted-for nitrogen could potentially end up in drinking water. This report eventually led to growers having to complete Irrigation and Nitrogen Management Plans (INMP) to examine how farming practices might impact groundwater quality. It was from this point forward the Western Region CCA program acquired new members at a rapid pace to become the largest regional program in the world. CCAs who took a course on nitrogen management were qualified to sign grower INMPs. The Western Region CCA program continues to maintain a strong membership while other regions in the U.S. are struggling. I have always felt being a CCA elevates a consultant to a higher level of service to their grower-customers. For California agriculture to continue to farm sustainably, a holistic approach is needed, and the CCA brings that expertise to the farm.

Future Challenges

As I look to the future of California agriculture, I see the biggest challenge being irrigation management. A great deal of attention is paid to how growers are applying fertilizer, but it is very difficult to encourage growers to improve their irrigation practices. I feel this challenge is due to growers receiving an invoice for their fertilizer but considering water to be their personal resource. It is quite challenging to understand water movement underground and how much water crops require to be fully productive. Many growers manage water based on hours of irrigation and do not consider the volume of irrigation being applied. Most crop advisors, I feel, are hesitant to comment if they see a grower’s irrigation practice is not appropriate for fear of liability. I feel the CCA program brings soil, water and nutrient management tools to bear on this complicated issue. Our strong and well-respected Western Region CCA program gives me hope that California will continue to sustainably produce a cornucopia of the world’s food and fiber for many years to come.