Citrus huanglongbing (HLB), previously called citrus greening disease, has been covered in thousands of articles. New technology and management tools continue to be discovered. Yet we still have no definitive cure and it could be a while before we see one. New rootstocks are surfacing, and treatment techniques are having some effect on slowing this devastating disease that has destroyed huge amounts of the world’s citrus trees.

As a Certified Professional Agronomist and a Certified Crop Advisor, I must prepare myself for HLB and its arrival here in the rest of California. It is currently here in one county. Many qualified scientists are approaching this menace with specific technologies, genetic modifications to trees, finding new resistant root stocks and of course trying to find something that will destroy the infections as well as a chemical or biological spray or injection that can combat and even cure the infection.

Others are addressing the psyllid vector, Diaphorina citri, that spreads the disease. Spray timings, mating disruptions, netting to cover the trees and keep the insect off them are being addressed.

Nutrition for Management

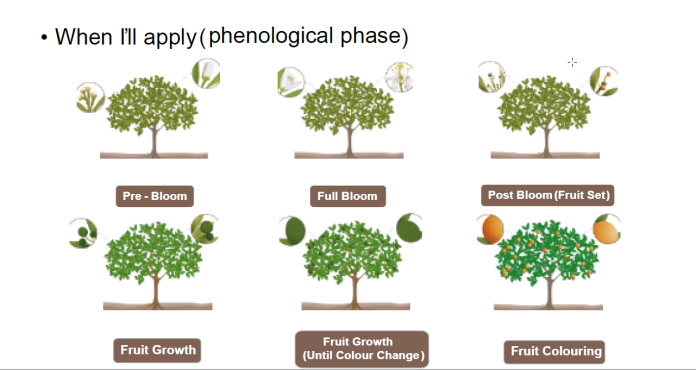

One approach I have used over the years mainly in Florida and Texas is based on years of repeated trials. It calls for using balanced and adjusted plant nutrition. It is most certainly not a cure, but I have witnessed improved yield, tree health, fruit quality and additional years of production from infected trees. It takes management and a deep knowledge of your citrus trees. When are the critical times of a developing tree, flower, bud development and fruit set, sizing, brix production and even color?

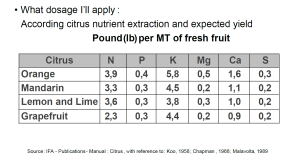

We need to study the amounts and most effective types of nutrients to apply. Balancing your crop nutrition is always critical, but a crop infected with the HLB needs special attention and application changes from a healthy crop nutrition program. A well-balanced program may handle these demands.

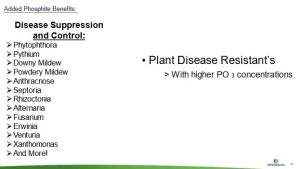

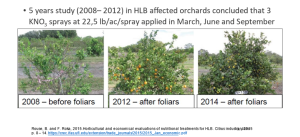

We must do more than a normal citrus nutrient program. One should understand the beneficial use of foliar applications of fertilizer nutrients and SAR (Systemic Acquired Resistance) products to maintain the health of HLB-infected trees. Several groves have maintained tree health and production by producing 7 to 10 years of profitable crops. The cultural production programs consist of a foliar spray cocktail of nutrients and SAR products applied three or more times per year to coincide with the initiation of vegetative growth flushes. The application of the nutrient/SAR foliage spray program can reduce and ameliorate HLB leaf symptoms and includes a good soil-applied dry fertilizer.

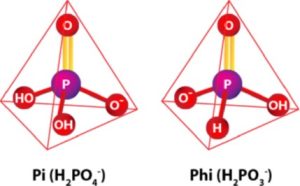

We know the movement of the bacteria inside the roots and leaves severely blocks the phloem tissue of these two areas. The interruption and restrictions to the movement of nutrients and sugars results in leaves dropping and remaining leaves being smaller. By using products that can stimulate or increase the efficiency of these affected areas, we should be able to improve movement of nutrients and sugars.

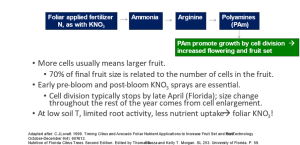

Research has shown that by applying potassium foliarly, we can improve the health and production of infected trees. Polyamines have also been shown to be effective.

Other Possibilities

If simply changing application methods and fertilizer sources can make major changes, we can start to imagine other possibilities.

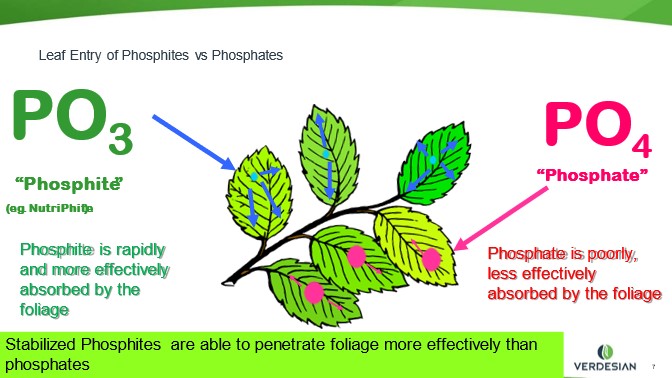

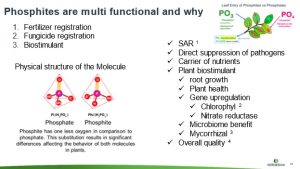

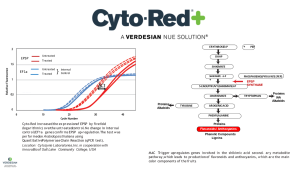

Verdesian Life Science has proven the use of phosphites can improve sugar and size in citrus fruit when compared to citrus trees not using this technology. Phosphites also trigger a plant’s own ability to increase its SAR. Plants have this ability to help them fight off infections.

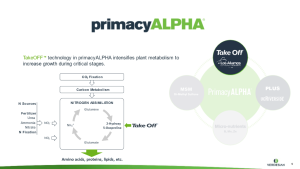

Verdesian also uses other proven biostimulant products such as Primacy Alpha that through foliar applications increase nitrogen assimilation. The increased effect on the glutamine/glutamate pathway increases production of amino acids, proteins, lipids and other essential building blocks in the plant. We have seen a consistent increase in new root growth. This could lead to a healthier pathway for water and nutrient uptake. Water uptake is essential to carry nutrients and provides much of the fruit weight.

With Primacy Alpha, we documented increased leaf size, chlorophyll production, and CO2 fixation which could offset the HLB effects on leaves. With the documented increased flowering, we might improve fruit counts. With consistent nitrogen uptake improvement along with whole plant biomass gains, we continue to successfully improve the health and production on healthy and stressed crops. Primacy Alpha also contains a cytokinin precursor. It triggers the plant to produce more natural cytokinin. Cytokinins play a role in cell division. More cells mean bigger fruit.

If plant growth, smaller fruit, leaf development, reduced chlorophyl production and activity plus phloem blockage are results of HLB, it stands to reason that stimulating and improving these restricted systems could benefit the affected crop.

Seeing the effect HLB has on fruit size and fruit color, we must seek ways to offset these things that reduce marketability of fruit.

Products such as Cyto-Red+, a unique blend of patented technologies, help support plant performance through chelation/complexation. MAC Trigger upregulates genes involved in the shikimic acid secondary metabolite pathway, which leads to production of flavonoids and anthocyanins, which are the main color components of the fruits.

I could spend days and thousands of additional words and examples to show how using plant nutrition and biostimulant could help at least extend the quality production on HLB infected citrus. It is not a cure but simply a temporary solution to continue producing fruit while we find a permanent solution.