Many California specialty crop production areas often face significant water supply curtailments due to recurring droughts and stringent environmental regulations. In this context, the utilization of field-specific information is crucial to enhance irrigation management practices and pursue profitable and high-quality food production under more pronounced weather vagaries and increasingly variable fresh water supplies.

The rapid adoption of pressure-compensating microirrigation systems during the last 15 years has enabled California winegrape growers to establish vineyards in areas with marginal soils and sloping terrains that otherwise were unsuited to other irrigation methods. While some degree of slope can be beneficial in vineyards for improved drainage of excess water, better airflow through the vines and faster escape of cold air to reduce the risks of springtime frost damages, it can affect microclimatic conditions, radiation interception, vine water use and sometimes influence grapes ripening.

Several researchers documented winegrape quality ties with irrigation management and grapevine water status (Jackson and Lombard 1993; Kennedy et al. 2002; Downey et al. 2004). The amount of irrigation water required to grow quality winegrapes and the frequency of irrigation applications depend on several site-specific factors, such as vine growth stage, vine and row spacing, vine density, size of vine canopy (Williams, 2001), soil texture and terrain characteristics.

Little information is available to growers about water use of vineyards on sloping terrains with different aspects. Such information is necessary as growers seek more resource-efficient production practices and vine water stress monitoring techniques to manage grape yield and quality, and as future water supplies become increasingly variable, uncertain, limited and costly.

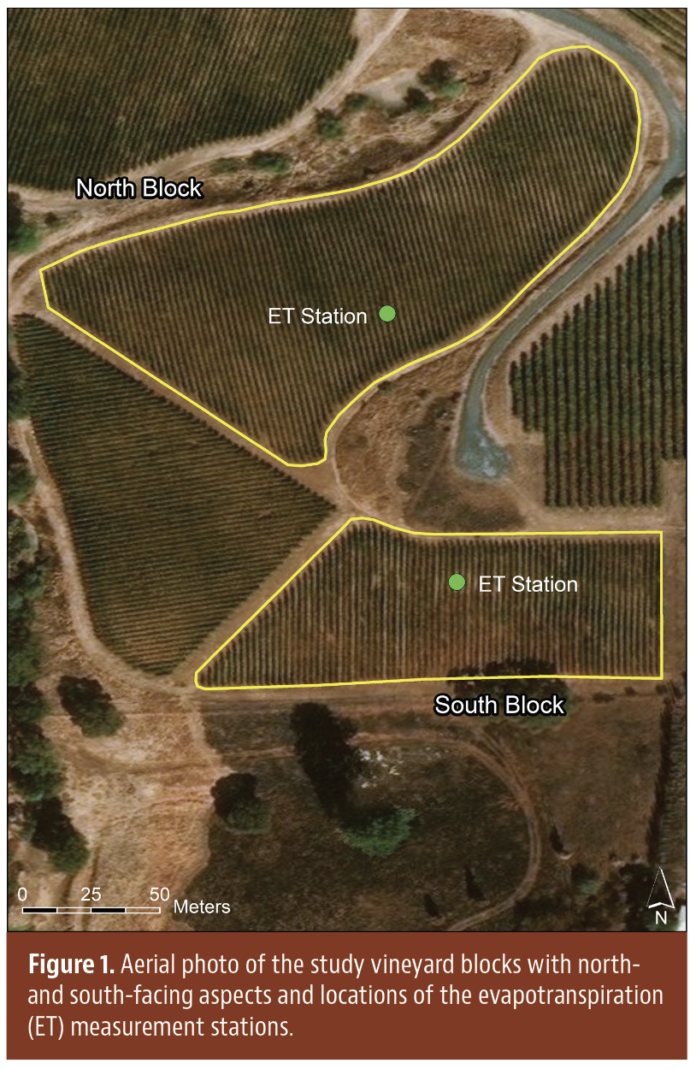

Recently, a team of UC researchers measured the actual grapevine evapotranspiration (ETa), its seasonal dynamics and vine water status in two winegrape vineyard blocks grown with microirrigation on sloping terrains with north- and south-facing aspects in El Dorado County during three consecutive seasons (2016, 2017, 2018). The goal of this field research study was documenting differences in grapevine water consumption (ET) due to slope and aspect for adapting irrigation management based on vineyard topography.

Study Site and Field Data Collection

The UC team instrumented two adjacent north- and south-facing commercial vineyard blocks (Fig. 1) located near Pilot Hill in El Dorado County for collecting field data of biophysical parameters. El Dorado County is in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains and is a relatively small but growing California winegrape production region falling within the California grape pricing district 10, where the top three varieties are Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah.

Both the vineyard blocks consisted of vines of Cabernet Sauvignon grafted onto 3309 Couderc rootstock, planted in 2000 at a density of 1,507 vines per acre and trained in a bilateral cordon vertical shoot positioned system with north-south vine row orientation. The vines were irrigated using single driplines with two pressure-compensating online button drippers per vine with nominal flowrate of 0.5 gph.

Both the north and south blocks had Auburn series very rocky loam soil with a typical depth of 2 feet, as mapped by the USDA-National Cooperative Soil Survey (California Soil Resource Lab 2019). The north-facing slope presented a different, shallower soil, with bedrock at 33 inches depth, but with less gravel content in the upper 20 inches and more finely textured clay retaining more moisture than in the south-slope soil. The terrain slopes in the north and south blocks were 24.5% and 25.5%, respectively.

ETa was determined with the residual of energy balance method from micrometeorological measurements of net radiation (Rn), ground heat flux and sensible heat flux obtained from one full-flux ET measurement station at each vineyard block (Fig. 1) consisting of a combination of eddy covariance and surface renewal equipment.

Actual crop coefficient (Ka) values were calculated dividing the measured ETa by atmospheric water demand (ETo) values obtained over the corresponding time-step from the automated weather station #195 (Auburn) of the California Irrigation Management Information System (CIMIS), according to the relation Ka = ETa/ETo.

The UC team assessed the vine water status during the three growing seasons with periodic measurements of the midday stem water potential on clear-sky days (between 11:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m.) using a Scholander-type pressure chamber on six vines per vineyard block (one fully expanded and shaded leaf per vine), which were randomly selected within the footprint area of each ET station.

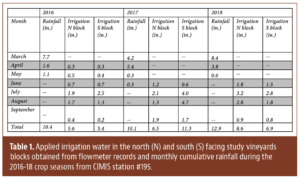

Table 1 reports the amounts of irrigation water applied in the north- and south-facing vineyard blocks, recorded with magnetic flowmeters during the three consecutive crop seasons and the monthly rainfall values recorded at the nearby CIMIS station. Differences in applied water were observed between the north and south blocks, which likely resulted from different application rates between the blocks but also from adjustments of irrigation frequency and duration based on visual assessment of vines’ and appearance. In fact, the vineyard manager applied irrigation water with varying frequencies and durations over the different months, the vineyard manager reported that irrigations for the two vineyards blocks were scheduled based on visual observations of the vines. The vineyard manager also considered the available soil moisture from periodic soil probing and existing water supply limitations.

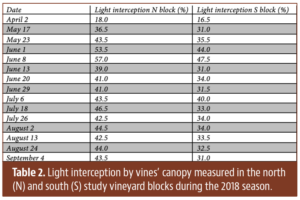

Light interception by the vine canopies was measured during the 2018 growing season using the ‘Paso Panel’ canopy shade meter (Battany 2009), which consists of a solar collector panel, a voltage meter and power switch attached to a portable frame. Holding the Paso Panel underneath the grapevine canopy for a few seconds allowed for measuring the voltage current generated by sunlight passing through the foliage and striking the panel’s surface as illustrated in Figure 2.

The current readings obtained placing the panel under vine canopies at multiple locations in the vineyards were then divided by current readings taken under full sun outside the vineyards to determine the shaded area by the vine canopy, which is a proxy of the vines’ fractional canopy cover. All the measurements in the north and south vineyard blocks were taken during clear-sky days at solar noon ± one hour and then calibrated against full-sun current readings. The values of shaded area by vines (%) were used to determine comparative differences in vines’ canopy growth and size between the north and south blocks.

Actual Grapevine Water Use for North- and South-Facing Blocks

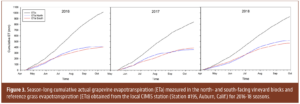

Figure 3 illustrates the ETa for the north and south vineyard blocks in 2016, 2017 and 2018 along with ETo. From the figure, it can be noticed that the north and south blocks had very similar season-long cumulative ETa values, but the time course of ETa differed between the two blocks during the three growing seasons. In the 2016 and 2018 growing seasons, ETa was slightly higher in the south block than the north block from April to early June, then ETa of the north and south blocks matched in late June. Afterward, the north block had slightly higher ETa from late June until late September to early October.

The field dataset of 2017 shows very similar seasonal cumulative ETa values for the north and south blocks, but differences in ETa can only be noticed for the period from late June to early September, with the north block having slightly higher ETa than the south block, which is consistent with the pattern of 2016 and 2018. From mid-September to late October 2017, the south block had slightly higher ETa than the north block, which reveals a contrasting pattern to that of 2016 and 2018. The higher late season ETa in the north block in 2017 was probably due to larger water applications that occurred during irrigation events in late July and August in the area surrounding the ET measurement station of the north vineyard, which likely resulted from a dripline leak going unnoticed for more than a month as reported by the vineyard manager and as revealed by the flowmeter records of 2017 (Table 1).

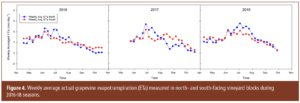

Figure 4 shows the time course of weekly averaged ETa values measured in the north and south vineyard blocks for the three seasons. In this case, slightly higher ETa was observed in the south block early in the season from April to early June in all three years; afterwards, higher ETa occurred in the N block during the central part of the season from early to mid-June through early to mid-August in all three years, whereas slightly higher ETa was observed in the south block relative to the north block in the late part of the season in 2016 and 2017. On the contrary, slightly higher ETa was observed in the north block relative to the south block during the late part of the 2018 season.

2016-18 seasons.

The data in Figure 4 clearly show vines in the north block expressed higher water use during the central part of the growing season, which is possibly related to higher interception of solar radiation during the period around the summer solstice, when the sun reaches its most northerly excursion relative to the equator. Higher water use in that period may also be related to the north block having relatively larger canopy size or accessing larger soil moisture reserves, thus facing less water limitations during the hottest part of the growing season.

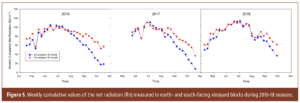

Figure 5 shows the weekly cumulative values of Rn measured in the north and south blocks during the study seasons. The Rn data show higher Rn values were measured in the south block during the early and late parts of the season in all three years, whereas Rn values were similar in both blocks in the central part of the growing season in 2016 and 2018, or slightly higher in the north than the south block in 2017.

Rn is the main force driving crop evapotranspiration. In detail, when soil moisture is abundant and can support vine water consumption without restrictions, higher Rn leads to higher grapevine ETa, all other factors (vines’ canopy size, light interception, available soil moisture) being similar. In the Mediterranean climate of northern California, these conditions normally occur in the period between March and mid-June, when grapevine growth is supported by abundant soil moisture resulting from late winter and early spring rainfall, thus there is no need to irrigate. Later, Rn still drives ETa, which is however dynamically regulated by the available soil moisture from irrigation and by the amount of radiation intercepted by the vines’ canopy. As such, the ETa pattern may not necessarily follow that of Rn, especially when vines face water stress because of deficit irrigation or because of difference in vines’ canopy size or soil moisture available to roots. In other words, multiple factors regulate the actual vine ETa, including canopy size, row orientation and available soil moisture as well as the angle of incidence of solar radiation, which in turn depends on the position of the sun along the growing season relative to vineyard topography (i.e., slope and aspect).

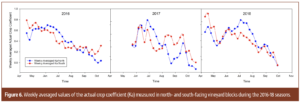

A good relative indicator of vine water use is the actual crop coefficient (Ka), which reflects the actual ETa rate relative to ETo. Figure 6 shows the weekly averaged grapevine Ka values calculated for the north and south blocks over the course of the three consecutive seasons. Ka integrates the atmospheric water demand with the grapevine’s physiologic processes, regulating the actual vine evapotranspiration alongside the plant-available soil moisture, thus providing synthetic information on actual grapevine water use in the site-specific and plant-specific conditions of the vineyard study blocks.

Figure 6 shows Ka was higher in the south block early in the season until mid-May 2016 and 2018, then the north block had higher Ka than the south block from early June to early August in all three seasons. Afterward, Ka was higher in the south block from mid-August to the end of the crop season in 2016 and 2017, whereas it was similar in the north and south blocks from mid-August to the end of the 2018 crop season. The figure also shows in 2016 and 2018 that Ka reached its peak values early in the season between mid-April to early May (whereas in 2017, peak Ka values were observed around late June) and progressively decreased during the course of the growing season, revealing increasing ETa reduction.

Following ETa or Ka could provide relevant information for tailoring irrigation management decisions (i.e., timing and amounts of water applications) based on actual grapevine water consumption, especially during periods of water supply restrictions. However, ET-based irrigation scheduling alone may not allow for targeting water stress levels that are conducive to reductions of grapevine vegetative growth and to specific fruit yield and quality targets.

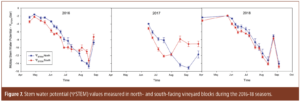

Some additional considerations can be drawn observing Figure 7, which shows the values of midday stem water potential (ΨSTEM) measured in the north and south blocks over the course of the three crop seasons. In all three years, ΨSTEM values decreased progressively from values between -2 ÷ -4 bars early in the season to values between -12 ÷ -15 bars towards the final part of the season, revealing vines in both the north and south blocks were exposed to increasing water stress. Vines in the south blocks had relatively lower (more negative) ΨSTEM values from April to early or mid-August in 2016, 2017 and 2018. ΨSTEM values were lower in the north block from early August to the end of the season in 2016 and 2017, whereas vines in the north and south blocks had similar ΨSTEM values from mid-August to the end of the season in 2018.

As far as plant water status is concerned, the relatively lower ΨSTEM values of vines in the S block in the first half of the crop season for all three seasons could possibly be due to higher environmental water demand on those vines (i.e., higher Rn). Similarly, the lower ΨSTEM values of north vines during the central part of the season was possibly related to higher environmental water demand in the north block due to similar incidence of solar radiation between the two blocks but higher light interception by the vines (resulting from larger vines’ canopy) in the north block. Alongside, the flow meter records showed larger irrigation water applications in the south block in late July and August 2016 and 2017, which possibly relieved some water stress on the south vines.

Table 2 reports the values of light interception by the vines’ canopy measured during the 2018 season in the north and south blocks, which reveal slightly faster vegetative growth and larger vines’ canopy size in the north than the south during the 2018 crop season.

According to Kurtural et al. (2007), faster canopy growth and larger canopy size in north-facing vineyards can be expected in Mediterranean climate as a result of relatively earlier bud-break and relatively lower impact of heat stress on vines relative to south facing slopes. All other factors being equal, in south facing slopes heat can increase during daytime above stress threshold levels, thus causing lower stomata conductance, less carbon assimilation and slower vegetation growth.

Controlling Water Use and Status at a Higher Level

Many winegrapes production regions have hillside vineyards, where the actual water consumption is affected not only by grapevine age and health, vine density, canopy size, row orientation and irrigation management practices, but also by the terrain slope and aspect. Topography affects the amount of solar radiation the vines receive and intercept, which is a major driving force of grapevine evapotranspiration under abundant soil moisture.

Irrigation scheduling for winegrape vineyards must consider multiple factors that regulate actual grapevine water consumption in order to maintain vine water status at specific target levels for limiting vegetative growth while pursuing fruit yield and quality objectives. Among others, vines’ canopy size, row orientation and available soil moisture to vines are major factors. However, the field datasets collected in the UC research study show vineyard topography factors (i.e., slope and aspect) also play a significant role in regulating ETa in hillside vineyards. As such, following an evapotranspiration-based irrigation scheduling with generalized crop coefficients derived from other locations and vineyard conditions may not be appropriate. Instead, following ETa and Ka determined for the site-specific vineyard conditions provides relevant information for irrigation scheduling decisions, but may not enable growers to pursue vine water stress levels that are desirable in specific stages of the growing season for achieving grape yield and fruit composition objectives.

Integrating weather- and plant-based irrigation scheduling approaches allows for higher level of control on grapevine water status that is necessary for grape yield, composition and quality purposes. For example, following ETa and Ka while keeping track of ΨSTEM values can provide more integrative information on actual vines’ evapotranspiration and water status for more precise irrigation management decisions.

In the field, ΨSTEM values can help decide irrigation timings more precisely, while ETa and Ka enable to determine adequate irrigation amounts for maintaining the desired water deficit levels to balance vegetative growth with grape yield and composition goals.

References

Battany, M.C., 2009. Estimating vineyard water use in the estrella-creston area of concern. Url http://cesanluisobispo.ucdavis.edu/files/71055.pdf

California Soil Resource Lab., 2019. Ssurgo (soil survey geographic), url https://casoilresource.lawr.ucdavis.edu/soilweb-apps

Cimis, 2018. California irrigation management information system, url https://cimis.water.ca.gov/

Downey, M.O., Harvey, J.S., Robinson, S.P., 2004. The effect of bunch shading on berry development and flavonoid accumulation in shiraz grapes. Australian journal of grape and wine research, 10(1), 55-73.

Jackson, D.I., Lombard, P.B., 1993. Environmental and management practices affecting grape composition and wine quality-a review. American journal of enology and viticulture, 44(4), 409-430.

Kennedy, j.a., Matthews, m.a., Waterhouse, a.l., 2002. Effect of maturity and vine water status on grape skin and wine flavonoids. American journal of enology and viticulture, 53(4), 268-274.

Kurtural, s.k., Dami, i.e., Taylor, b.h., 2007. Utilizing gis technologies in selection of suitable vineyard sites. International journal of fruit science, 6(3), 87-107.

Williams, l.e., 2001. Irrigation of winegrapes in california. Practical winery & vineyard, 23, 42-55.