Grapevine Red Blotch associated Virus (GRBaV) is the causal viral agent responsible for Grapevine Red Blotch Disease. This pathogen negatively impacts grape production by reducing fruit quality and yield. It can cause several physiological changes in vines, including changes in leaf color, reduced ripening speed and decreased fruit quality from reduced sugar and anthocyanin accumulation in the grapes. This reduction in fruit quality can lead to reduced market value, affecting the profitability of an impacted vineyard. The degree to which GRBaV will impact fruit quality and yield can vary from year to year within a vineyard but increases with the percent of infected vines contributing to the harvest. The exact mechanism by which Red Blotch reduces sugar accumulation in grape berries is still unclear; however, the available evidence suggests the virus affects the expression of genes involved in sugar transport and metabolism as well as in hormone signaling pathways that regulate sugar accumulation in grape berries.

Red Blotch disease was first discovered in Napa Valley, Calif. in 2008 when it was realized to be a new disease separate from leafroll which also causes similar red leaf symptoms as well as a reduction in fruit quality and yield. The similarities between the effects of Red Blotch and leafroll viruses likely played a role at masking the presence of Red Blotch virus until efficient virus screening techniques for GRBaV were commonly employed. At the point of its discovery, Red Blotch disease was not a newly emerged viral disease but rather a viral disease new to our recognition as a viral disease. Due to the misidentification of GRBaV in symptomatic grapevines, the virus may have been widely spread across California by the time a screening procedure was developed to identify its presence in plant tissues. To this point, Red Blotch virus was detected in herbarium samples collected several decades before the formal recognition of the virus. Red Blotch virus is the only member of the genus Grablovirus within the family Geminiviridae and has been separated into at least two clades of distinct strains of the virus. While originally recognized in California, it has since been found in several grape-growing regions worldwide. Grapevine Leafroll-Associated Disease, on the other hand, is caused by one of six viruses from the family Closteroviridae.

Grapevine Leafroll-associated Virus (GLRaV) is one of the most important viral diseases affecting grape production worldwide. Of the six viruses associated with leafroll disease, GRLaV-3 in the genus Ampelovirus is the most predominant; GLRaV-2 has also been noted as impacting large numbers of California’s vineyards.

Leaf Symptoms

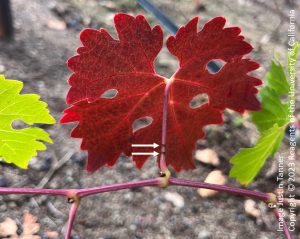

Often described as beautiful fall color by visitors to the vineyard around harvest time, the development of red leaves in red grape varieties is a sign the vines are not healthy. The most prominent visual symptoms of Red Blotch are reddish-pink blotches or patches that appear on the leaves of infected red grape varieties. These blotches usually appear later in the growing season, usually after véraison, first appearing on older leaves near the bottoms of shoots and later developing on leaves higher up the shoot. These blotches are irregular in shape and often have a mosaic pattern. Foliar symptoms of GRBaV and GLRaV are visually similar, and both result in red- or yellow-toned tissue of the leaf blade depending on the grape cultivar. With Red Blotch, the leaf veins also turn red which is in contrast with leafroll in which the veins remain green. Another subtle difference is that Red Blotch does not distort the shape of the leaf causing the leaf blade to remain flat while Leafroll-associated viruses can cause some leaf blades to roll down along the margins, resulting in a downward curl. When a vine has Grapevine Red Botch Virus and a Grapevine Leafroll-associated Virus, leaf symptoms usually present as typically expected for Grapevine Leafroll associated Viruses with leaves showing green veins and some degree of leaf rolling. Towards the end of the season, symptomatic leaves from either virus may turn completely red, complicating visual diagnosis. In white varieties of grape, both viruses are much less conspicuous as the leaves do not turn red but may present in a subtle, yellow-chlorotic, patchy pattern.

Virus Spread Through Infected Material

Both viruses can be transmitted through propagation of infected planting material. The use of CDFA-certified virus-tested vines is an important initial step in excluding viruses in your vineyard. As there is currently no cure for vines once infected with Red Blotch or Leafroll, the use virus-free planting materials and the removal of infected vines is the first line of defense in virus management. Scouting and monitoring vineyards for red leaf symptoms in the fall is essential for early detection. PCR testing can be used to confirm viral presence in visually identified symptomatic vines if there is any doubt about the symptoms and is especially useful for confirming virus status of white grape cultivars. Once identified, infected vines should be rogued from the vineyard to reduce pathogenic inoculum and prevent them from serving as a source of virus that could inflect healthy vines. Vines identified in the late part of the growing season should be removed before the start of the next season to minimize the spread of the virus by insect vectors.

PCR-based testing methods are the standard for determining virus status of individual vines with a high degree of accuracy but becomes cost-prohibitive at commercial scales. New approaches to virus identification are being developed to allow for screening of vines rapidly and accurately within a whole vineyard. The use of drone-based hyperspectral imaging has been demonstrated to be more accurate at identifying vines infected with Red Blotch or Leafroll compared to visual scouting by experts when coupled with machine learning methods. Another approach in development involves the use of dogs trained to detect virus in vines. Other methods in development include non-destructive wavelength transmission and reflection to identify foreign organisms within the vine without damaging the plant.

Virus Spread by Insect Vectors

The three-cornered alfalfa hopper (Spissistilus festinus, TCAH) is currently the only confirmed vector of Red Blotch virus. It is an insect that can feed on many plant species including grapevines and is widely distributed throughout the U.S. Plants such as alfalfa and other legumes serve as the preferred hosts for TCAH; however, as these plants dry up over the season, TCAH will migrate onto less preferred hosts such as grapevine. This pattern of micro-migration may be particularly problematic in vineyards where annual cover crop decline occurs near the beginning of vegetative growth for grapevines. TCAH can acquire GRBaV from feeding on infected plants and subsequently spread the virus to healthy vines. However, studies investigating the vector-capacity of TCAH have found they are not good at spreading the virus. TCAH is a circulative and non-propagative host where the virus does not replicate within the insect but is transferred into the salivary glands. TCAH requires an extended acquisition period of about 10 days to uptake the virus while feeding on infected vines followed by an extended inoculation access period of about four days of feeding on healthy vines to spread the virus. As grapevines are not the preferred host, TCAH populations usually remain low within vineyards and are mainly driven by the presence of legumes in cover crops. Timely management of cover crops by tillage before TCAH reaches adulthood may help reduce population sizes and limit virus spread by the alfalfa hopper. Additionally, removing unmanaged grapevines from the perimeter of vineyard areas is helpful as these vines can act as virus reservoirs and are particularly at risk of infection in riparian areas where insect populations may be higher. The work of identifying and confirming insect vectors of Red Blotch is ongoing, and there are many other insects identified as potential vectors currently under investigation.

Due to the feeding nature of TCAH, alternative plant hosts of GRBaV should be identified in California and managed to reduce potential inoculum sources near vineyards. To date, few endemic plant species within California have been tested to see if they can harbor GRBaV. However, researchers tested 13 species of woody, herbaceous plants from riparian areas which tested positive for GRBaV and identified two positive hosts: Himalayan Blackberry and a wild grapevine hybrid (V. californica x V. vinifera). In certain regions of California, a higher number of inoculum sources and alternative hosts for GRBaV may lead to higher pathogen pressure in vineyards with Red Blotch symptoms. With the potential for other insect vectors being able to transmit GRBaV, it is important to understand which plants in vineyard-adjacent ecosystems can increase risk of Red Blotch transmission into grapevines.

For Leafroll, several species of mealybugs (family Pseudococcidae) and scale insects (family Coccoidea) have been shown to be competent vectors. However, the most important vector of GLRaV is the vine mealybug (Planococcus ficus), an invasive species first detected in California in the mid-1990s which can have up to seven generations in a single growing season. The vine mealybug requires a period of as little as 15 minutes of feeding on an infected vine to acquire Leafroll. Because of the efficiency of virus uptake by the vine mealybug and the rapid nature of its reproductive strategy, in areas where vine mealybug is present, Leafroll has the potential for rapid spread. The most effective management strategy for vine mealybugs involves an integrated approach which includes the use of biological, cultural and chemical control methods as well as managing ants which protect mealybugs from their natural enemies. The parasitoid wasp Anagryus pseudococci and other beneficial species have been shown to successfully reduce vine mealybug infestations to manageable levels. A detailed guide to this approach is available at ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/grape/vine-mealybug/.

In summary, both Red Blotch and Leafroll viruses can cause significant impacts to fruit quality and yield. Both viruses will cause symptoms of red leaves in red grape cultivars; however, slight differences between these symptoms can be visually identified and useful in distinguishing between the two. Once symptomatic vines are identified, PCR testing can confirm virus status. While both viruses can be vectored through the propagation of infected material, there’s great differences in the efficiency of virus spread by insect vectors. For Red Blotch, the three-cornered alfalfa hopper, requires an unusually long acquisition time of about 10 days of feeding on infected vines before it can spread the virus compared to the alarmingly quick uptake of Leafroll by the vine mealybug in around 15 minutes. Other potential insect vectors of Red Blotch have been identified and are currently under investigation. Additionally, the three-cornered alfalfa hopper usually doesn’t reach high populations within vineyards as the grapevine is not it’s preferred host plant; while the vine mealybug, on the other hand, due to its prolific reproductive strategy has the potential to reach very high numbers if left untreated in the vineyard. Once infected with Red Blotch or leafroll, there is no cure, and removal of the vine is the only sure way to prevent future spread to neighboring vines. Monitoring GRBaV symptomatic grapevines and removing them from the vineyard quickly may be the best approach to limiting the spread of Red Blotch at the moment. With research ongoing and without a clear understanding of how the virus can rapidly spread, reducing inoculum sources is a proven, preventative strategy.