There are a number of options for controlling—or at least limiting the damage of—birds in vineyards, but experts say the best defense is to build a strategy that includes multiple points of protection and mix it up.

The extent of bird damage within a vineyard depends on vineyard site location, varietal and other variables, as well as bird species. UCCE Viticulture Farm Advisor Glenn McGourty in Mendocino County said birds can be a particular problem on vineyards located along the edges of wildland areas. Particularly in those situations, the best protection is to create a barrier around the vines such as netting. He said woven polypropylene netting works best in his region and experience.

Birds begin to feed on grapes in vineyards as fruit turns color and starts to ripen. In McCourty’s north coast winegrape region, early ripening red varieties such as Pinot Gris, Cielogiolo and Pinot noir are among the favorites, he said. Birds feed around the clock during the day but are particularly voracious in the early morning.

Protecting the Crop

UC Cooperative Extension Wildlife Specialist Roger Baldwin said netting appears to be the most effective, and most expensive, option for controlling grapes in problem areas.

“Netting is used in areas where the grower expects substantial grape loss in the vineyard, and the crop is relatively high in value,” Baldwin said.

Another effective option is using birds of prey as a natural bird deterrent. Baldwin said preliminary research shows that falcons can prove to be a good deterrent and provide “fairly substantial reduction” in crop loss.

“Falconry is a pretty effective tool but it too is pretty expensive. While it’s a little less expensive than netting, it also should be used in higher value cropping areas,” Baldwin said.

McGourty agreed falcons can be effective in his high end vineyard area, particularly in larger vineyards.

“Falcons work quite well, but are expensive, starting at about $20,000, so you need about 500 acres to make it pencil out,” McGourty said. While netting and falconry are two effective options for controlling birds, they can be cost-prohibitive for smaller or lower value vineyards.

One lower-cost control is to put a human in the vineyards with a shotgun, but that comes with both regulatory and public/neighbor relations considerations. Invasive pests, such as starlings don’t require specific depredation permits, while most native and migratory species, including house finches and robins, will require permits through state and federal wildlife agencies to remove birds through shooting or trapping.

cause significant damage to grapes (photo courtesy UC Regents.)

Many growers rely on frightening devices that use auditory or visual hazing, such as propane cannons or electronic sound transmitters. Visual devices such as reflective mylar streamers, scare-eye balloons and even air dancers can provide some benefit for brief periods of time. Baldwin said auditory devices must also provide variety and target specific bird populations in the vineyard to maintain their effectiveness.

Know Your Birds

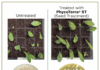

Baldwin said an overall program should take into account what type of birds are in the vineyard and the corresponding damage, which will vary by species. Starlings can cause extensive damage, for instance, plucking off and eating the whole berry and damaging neighboring berries with their feet. House finches tend to peck at berries and tear them open, which can lead to secondary disease problems such as bunch rot from juices dripping on berries below. It is important to have someone who is experienced at identifying bird species looking at the damage and keep track of what is in the vineyard year to year, as with most pest issues, he said.

lead to secondary disease problems such as bunch rot from juices dripping on berries below (photo courtesy UC Regents.)

Generally, Baldwin noted, migratory birds are more susceptible to frightening devices because they typically only loiter in one place for a week or two. For more resident or semi-permanent populations, the UC IPM manual suggests combining visual devices such as mylar strips, with auditory devices such as propane cannons. The key to success is to mix things up so that birds don’t become habituated to the hazing device, Baldwin said.

“Loud noises like propane cannons and shell crackers can be effective at deterring birds from a given area for a short period of time,” he said. “What we generally recommend is growers would mix and match some of these tools. Maybe use propane canons for five to six days then when birds habituate, move to electronic distress calls, then incorporate visual hazing devices, and so on. You can’t just put mylar streamers out there and think you are going to solve the problem, and you can’t just put propane cannons and think that will solve the problem; you have to be smart.”

One auditory hazing device, Bird Gard, relies on what the Sisters, Ore.-based company calls “bioacoustics” to randomly produce calls of naturally occurring local dominant predator birds combined with resident pest bird distress and alarm calls. All sounds are customized to repel the specific birds within a particular vineyard. Since the species of pest birds can change during the season, each unit contains a changeable sound card that is customized to vineyard location and the type of pest bird in the vineyard.

“Bird Gard has been around for over 30 years. In our early stages of development, we learned pretty quickly that birds habituate to the same sound played over and over,” said Quay Richerson, California sales director for Bird Gard. “So, we developed a microprocessor within our circuit board that randomizes the order in which sounds playback, the frequency of the sounds, and the intermittent time-off period. The keyword there is randomized. The sounds have to keep changing all the time for it to have the effectiveness we desire.”

Quay said that to protect the crop as sugars come on, growers should ensure the Bird Bard units are operating two weeks before veraison and run through harvest.

Baldwin said growers can usually get three to four weeks of protection with a strategic program, so they should wait to put defenses out until close to when feeding begins to get control through harvest. The decision on when to start implementing bird strategies is largely site specific. Individual growers should look at the previous year’s bird damage and crop value to figure out if and when it is time to spend the money on bird control.

“It’s best to begin before birds start coming and feeding in those fields, but you don’t want to begin too soon because each control measure will only last so long,” Baldwin said.

New Technologies

While some bird control measures are as old as farming, newer measures are looking at integrating technologies to outsmart one of grape production’s smart pests. New research is being done on devices that create background noise that interferes with birds’ ability to communicate with each other. Feeding repellents are also in trial, though that technology is in its infancy. In addition, drone technology is also being researched.

Dr. Page Klug, Supervisory Research Wildlife Biologist with the USDA National Wildlife Research Center at the North Dakota Field Station, has conducted evaluations of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) as a tool to protect agricultural crops from bird damage.

UAS are known to elicit behavioral and physiological responses in wildlife and have been proposed as a means to protect crops from birds. Klug evaluated behavior responses of blackbirds to fixed wing and rotary wing drones on a number of platforms and hazing methods.

The birds showed no response to the fixed wing UAS but did show a response to the rotary UAS and responses were more pronounced with lower altitude approaches.

Klug concluded that the rotary UAS has the potential to modify bird behavior in a way that may reduce crop damage, but emphasized in her research that no studies have been done to assess potential effectiveness.

Klug said that to be effective in protecting crops from blackbird depredation, modifications to the physical UAS might be needed. Modifications include the addition of an audio system to produce distress or alarm calls or firearm discharge sounds, adding lasers or lights or shapes that mimic an aerial predator.

In addition, a fully automated UAS may be a more effective strategy. This modification could potentially reduce labor, Klug wrote, The UAS could also be programmed to fly patterns which would be most likely to deter birds. Environmental conditions also come into play with UAS use as low temperatures can affect battery packs. Klug noted that their evaluations were done with specific UAS models and other types of drones and responses by birds to approaching UAS can vary based on the specific platform and are likely species and context specific.

While growers have access to a number of measures for controlling what can be one of a vineyard’s most perplexing pests, an effective program is not “set it and forget it” experts said. An effective program should be customized and managed according to each specific site, taking into consideration the bird pests present and the size and value of the vineyard and grapes.