If you ask tomato growers in the northern San Joaquin Valley what the most seen disease in 2021 is, beet curly top virus (BCTV) is the one that stands out. Undoubtedly, we have seen an exceptionally high incidence of BCTV on processing tomatoes vectored by the beet leafhopper (BLH). From April to July, most farm calls were about the curly top virus infestations in tomato fields in San Joaquin and Stanislaus counties. Not only in the northern San Joaquin Valley, similarly alarming reports also came from the southern San Joaquin and lower Sacramento Valleys. The unusually high incidence of BCTV in the Central Valley seems to be associated with drought, which likely has caused an earlier withering of the vegetations on the foothill that led to the earlier migration of BLH down the valley.

The Vector: Beet Leafhopper

BLH, Circulifer tenellus (Baker), has a typical leafhopper wedge-shaped body with tapering posterior. An adult BLH is approximately 1/8-inch long and has a distinct and broad head with a rounded anterior margin (Fig. 1). The adult BLH body color varies from olive green to light tan, with small dark-brown and black markings. Although BLH is believed to have originated in the Mediterranean region, its presence in North America has been reported for over a century ago. In the U.S., it is considered a serious pest of several crops in semi-arid and arid areas of the southeastern and western states, including Colorado, Washington, Oregon, Utah, Idaho, Arizona and California.

BLH has multiple generations per season, with up to five generations reported in California. BLH has numerous weed and crop hosts that are common in the Central Valley. Adult leafhoppers overwinter in the foothills. As the temperature warms up in February and March, the overwintered females lay eggs in various early weed hosts, such as pepperweed and desert Indian wheat in the foothills, and complete the first generation (and partial second generation in some years) before the vegetation dries. The first-generation nymphs acquire BCTV through direct feeding on the infected early season weed hosts, and the newly emerged virus-carrying adults migrate down to the valley.

The migrating adults feed or probe on summer weed hosts such as Russian thistle, London rocket, annual saltbush, goosefoot, lamb’s quarters, pepperweed, filaree, redroot pigweed, etc., and cultivated plants such as sugar beet, bean and tomato. Several leafhopper generations are produced before the maturity of the weeds or crop harvest. The leafhopper populations from the summer generations can transmit the curly top virus to the host crops, such as processing tomatoes, and produce disease. Unfortunately, there are no processing tomato commercial varieties that are resistant to BCTV. In 2021, due to unusually dry springtime, likely BLH migration to the valley occurred early, which might have contributed to the increased BLH abundance and curly top disease incidence in tomatoes.

Vector and Virus Interaction: Disease Transmission

BCTV is taxonomically in the genus of Curtovirus within the family of Geminiviridae, containing a single-stranded circular DNA. BCTV is currently known to be only vectored by BLH and has over 300 host plant species in the western U.S. The virus must be inoculated from diseased to healthy plants by BLH feeding. So, there is no risk of disease spread from one plant to another without the insect vector involved. The mechanism of virus transmission by BLH is called circulative persistence transmission.

The leafhopper ingests the virus from the phloem of the infected plant. The virus circulates through the insect blood (hemolymph) and finally reaches the insect’s salivary gland. When the insect feed on the healthy plant, the virus passes down to the healthy plant through saliva. The virus circulates within the insect body but does not multiply. The virus-infected BLH is an efficient vector and can transmit BCTV within a minute of feeding as it has a ready-to-go virus load in its salivary gland. On the other hand, once a healthy leafhopper picks up the virus from a diseased plant, it takes about four hours for that leafhopper to be infective (i.e., incubation period). Also, infected leafhoppers cannot transmit the virus through the egg to their progenies.

Since BLH probe and feed on multiple hosts that appear in their flight path indiscriminately, the degree of disease incidence varies among tomato fields. Although it seems that field margins or isolated plants with exposed soils are more vulnerable, we did see clusters of infected plants in the middle of tomato fields (Fig. 2). Once fed and inoculated by BLH, tomato plants begin to exhibit purpling of veins and stunting within two weeks (Fig. 3). After infection with BCTV, younger plants usually die, while plants infected at a later stage may survive, but premature green fruits, if any, will turn red (Fig. 4). Regarding the yield loss, a field with a BCTV incidence below 5% may still reduce productivity if several diseased plants emerge next to each other in multiple rows (Fig. 5).

Field infestations over 10% are more likely to cause significant yield losses. CDFA has an active statewide control program by applying insecticide to the western foothills using a threshold (treatable if the sweep net sampling produced a minimum of eight BLH per sweep.) However, the sporadic occurrence of BCTV and likely presence of the population below the treatment threshold makes the control sometimes challenging as there might be a lot of areas left out without treatments due to the mild leafhopper populations based on that sweep net sampling. Eliminating host weeds before transplanting and during the season as well as delaying tomato planting are usually tried. Insecticide application to control the BLH population may reduce disease spread even though infested plants will not recover. More detailed information can be found at ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/tomato/Beet-Leafhopper/, ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/tomato/Curly-Top/, and cdfa.ca.gov/plant/IPC/curlytopvirus/ctv_weekly_reports.htm.

Collaborated Study with California Tomato Research Institute

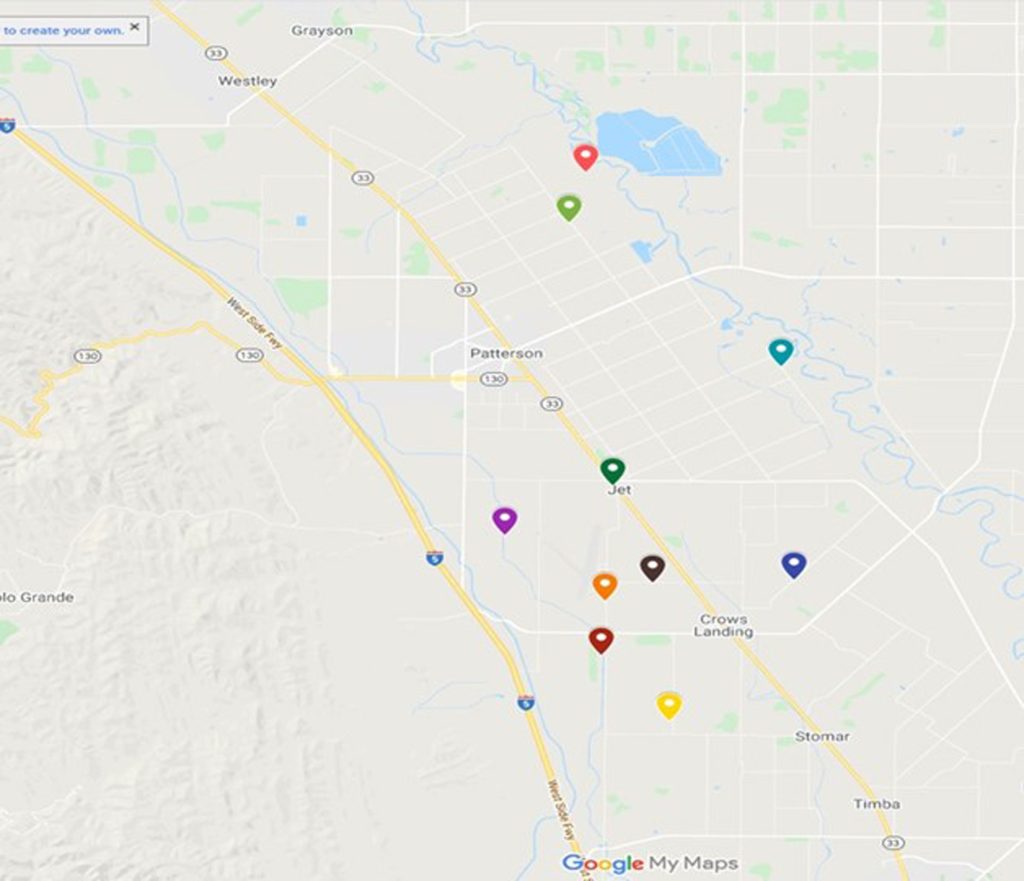

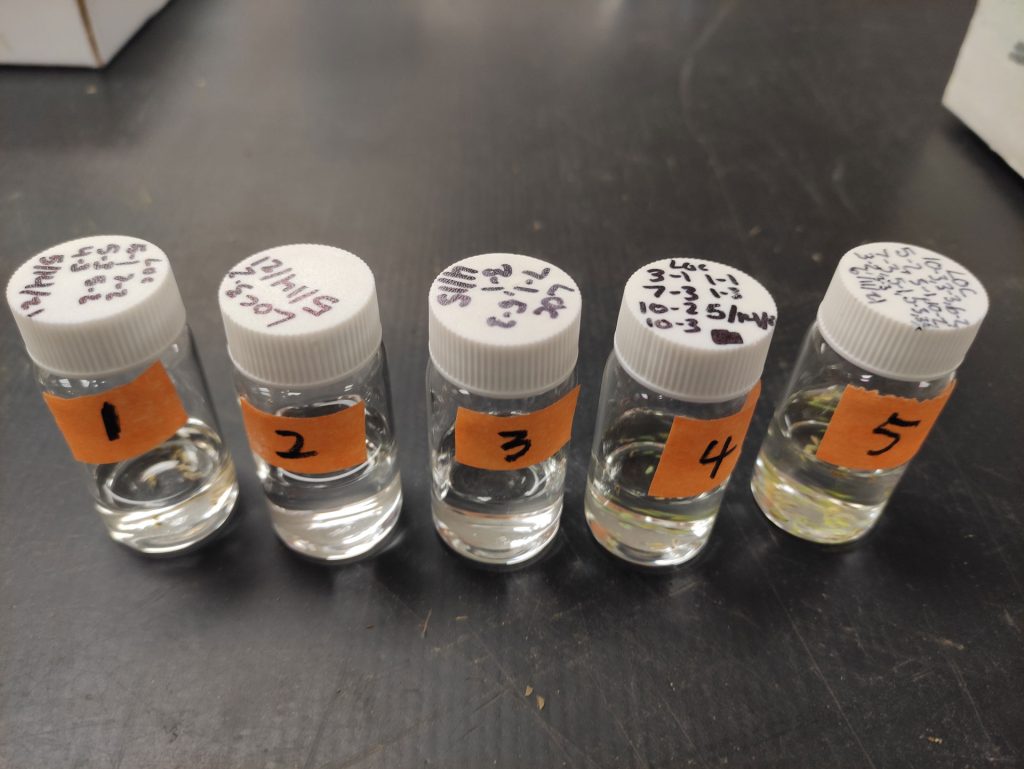

With the California Tomato Research Institute (CTRI) funding support and in collaboration with the CDFA’s BCTV Control Program, we began a research project to monitor BLH population dynamics and BCTV incidence in processing tomato fields. To monitor BLH activity, we set up yellow sticky traps on 4-ft-tall metal posts at 10 different locations near 22 processing tomato fields along the highway-33 corridor in Stanislaus County (Figs. 6 and 7). The gross acreage of the monitored tomato fields is 2,180 acres. During the study, we replaced sticky traps biweekly and took sweep net samples monthly. By inspecting collected traps and sweep net samples, we submitted all suspicious BLH together with diseased tomato tissues to the CDFA-Integrated Pest Control and UC Davis for laboratory confirmation prior to estimating BLH population and BCTV incidence at each monitored location (Fig. 8). As fields are being harvested, we will work closely with growers to estimate the potential yield loss. Besides the 22 monitored fields, eight additional tomato fields which were not part of the study were also reported for BCTV infection by growers or their PCAs.

Current results indicated that of all the 10 monitored sites (22 fields), six sites, including 14 tomato fields, were identified to have a BCTV incidence of 5% to 10%. The disease incidence levels of 0% to 5% and >10% were found in the remaining eight monitoring fields. For the additional infested fields reported by growers and PCAs, three, four, and one fields had estimated 0% to 5%, 5% to 10% and >10% BCTV, respectively. The complete results of this study will be reported later in the year.