Invasive pests can wreak havoc on orchards, and keeping them in check often means frequent pesticide applications. With increasing pesticide regulations and the rising costs of chemical applications, growers of all crop types need reliable alternatives for controlling key pests. Our research explores one such strategy: leveraging natural habitat to enhance pest control. By studying how natural vegetation, including both large protected areas and smaller on-farm hedgerows, impacts pest control, we’re asking how strategically incorporating native plants into an operation may reduce pest pressure and potentially cut down on pesticide use.

Small-scale plantings like hedgerows and floral strips have frequently been found to improve biological pest control and attract pollinators but there are challenges to implementing these approaches. First, some studies have shown small-scale plantings only deliver better pest control when they are within 100 to 1,000 meters of larger patches of natural vegetation (Chaplin-Kramer et al. 2011; Heath and Long 2019) and may thus be less effective in simple habitat-poor landscapes. Other studies also show substantial variation in the effects of natural vegetation on pests, natural enemies and crop yields (Karp et al. 2018). Sometimes adding natural vegetation works great but other times it seems to have no impact. This variation makes it difficult to develop broadly applicable management guidelines.

These inconsistent effects of noncrop vegetation on pest levels and crop yields might be attributed to the following explanations:

1. Researchers failing to monitor the entire biological control community and thus overlooking key interactions.

2. A poor understanding of how on-farm practices interact with landscape-scale processes.

3. Measuring pest levels and biological control in ways that are not relevant to the economic decisions made by growers (Karp et al. 2018, Chaplin-Kramer et al. 2019). For growers to determine whether natural vegetation is likely to deliver useful biological control and reduce expenditures on pesticides, we need studies that comprehensively survey the entire community of animals providing biological control, integrate experiments at the farm and landscape scale and measure biological control in a way that fits within the framework growers already use to make pest management decisions.

Ventura County Study Targets Orchard Pest Control

We have recently begun a study in lemon and avocado orchards in Ventura County, where we are assessing whether natural vegetation can suppress arthropod pest outbreaks below economic thresholds. We are compiling data on pest levels in orchards using both our own standardized surveys and data collected by PCAs. We are also comprehensively surveying the wildlife community that may contribute to pest control, including bats, wild mammals, birds and insect natural enemies. Critically, our study design allows us to assess how farm-level practices interact with landscape-scale variables. Half our study orchards are close to a large riparian corridor with extensive natural vegetation and half are more than 1 kilometer away. Additionally, half our orchard survey sites have bare margins and half have vegetated margins. This study design enables us to assess how both small on-farm plantings and large patches of natural vegetation interact to influence pest levels and wildlife abundance and diversity. We are also evaluating which specific plant species and plant traits in hedgerow plantings attract helpful insect predators, insectivorous birds, parasitoids and pollinators.

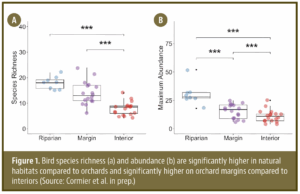

This study is in the early stages, but several key preliminary results have emerged. First, birds can be pest control allies. In orchards close to large patches of natural habitat, we found significantly more insect-eating birds like yellow-rumped warblers and bushtits. These species are known to consume pest insects like aphids, scale and ants. We found no evidence of bird damage to crop trees or fruit, but these effects will vary depending on crop type because avocado and lemon are not species typically targeted by birds. The diversity and abundance of beneficial bird species was significantly higher on orchard margins than interiors (Fig. 1). Additionally, bird diversity and abundance were significantly higher in orchards that had small patches of natural vegetation on their margins even if they were far from the large riparian zone. If you or your grower have natural vegetation nearby, you may already have a hidden pest control workforce, and growers might be able to attract more of these workers by planting the right vegetation on margins. We are currently analyzing exactly what vegetation characteristics attract beneficial insectivorous birds with the aim of providing precise guidance on how to put birds to work on farms.

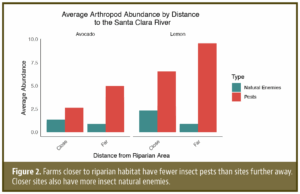

We also find that hedgerows and floral strips attract the right bugs. Large patches of native vegetation and noncrop habitat around orchards bring in more beneficial insects, including wild bee pollinators and predatory parasitoid wasps. The closer orchards were to the large riparian zone, the stronger this effect. Our orchards close to the river had both fewer pests and more parasitoids (Fig. 2). We are curious if growers who have hedgerows experience increases in pest populations and pesticide costs. This might tell us if intentional hedgerow plantings harbor pests and will be a key future analysis.

A major concern for growers is whether adding native plants could inadvertently attract more pests. The good news? So far, we haven’t seen an increase in pest populations in orchards with hedgerows or floral strips. In fact, we see evidence for greater abundance of pests in orchards that are farther from the riparian zone (Fig. 2). We also anecdotally heard some growers needed fewer pesticide applications in blocks closer to natural vegetation.

Actionable Strategies for Growers and Consultants

Our study suggests some practical tips for incorporating native vegetation into farms. First, start small. Even a 10-by-10-meter hedgerow can make a difference over time when it comes to diversifying habitat for beneficial species. Choose native species that attract beneficial insects like buckwheat and salvias. Adding species with woody structure like laurel sumac, coyote bush and willows can attract birds that need cover and places to perch and nest. Second, think year-round by selecting plants that provide bloom year-round so that you can provide pollen and nectar for insects outside of your crop’s bloom period. Check out this UC site for more information on planting a hedgerow: ucanr.edu/sites/default/files/2018-12/295420.pdf. Finally, monitor and adapt. Keep an eye on pest levels and beneficial insect activity. Work with your PCA to track changes and adjust as needed.

Our study is ongoing, but early results suggest integrating natural habitat into pest management strategies could be a cost-effective way to enhance biological control. Healthier landscapes and support for beneficial insects go hand in hand.

Interested in learning more about our study? Reach out to us! We are a group of researchers from Cal Poly, Pomona, UCCE, CSU Long Beach and UC Santa Barbara with backgrounds in entomology, ecology, animal behavior and restoration. Any questions can be directed to Liz Scordato, Hamutahl Cohen and Erin Questad at escordato@cpp.edu, hcohen@ucanr.edu and ejquestad@cpp.edu, respectively.

References

Chaplin‐Kramer, R., O’Rourke, M. E., Blitzer, E. J., & Kremen, C. (2011). A meta‐analysis of crop pest and natural enemy response to landscape complexity. Ecology Letters, 14(9), 922-932.

Heath, S. K., & Long, R. F. (2019). Multiscale habitat mediates pest reduction by birds in an intensive agricultural region. Ecosphere, 10(10), e02884.

Karp, D. S., Chaplin-Kramer, R., Meehan, T. D., Martin, E. A., DeClerck, F., Grab, H., … & Wickens, J. B. (2018). Crop pests and predators exhibit inconsistent responses to surrounding landscape composition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(33), E7863-E7870.