Listen to the audio version of this article (generated by A.I.)

Introduction

Weeds are one of the most persistent and costly challenges in perennial cropping systems, including orchards, vineyards and berry plantings. Permanent plantings limit management flexibility, creating stable ecological niches that favor perennial and other hard-to-control weed species. Weeds not only compete with crop trees and vines for water, nutrients and light, they also interfere with irrigation, complicate harvest, increase frost risks and serve as refuges for pests and pathogens.

Herbicides are the primary tool for weed control in perennial crops. However, herbicide resistance, limited availability of registered products, regulatory pressures and increasing concerns about safety and off-target effects are challenging the sustainability of a chemical-only strategy. Even effective herbicides can perform inconsistently under adverse environmental conditions. These constraints have accelerated efforts to identify alternative tools that provide dependable control, improve resistance management and align with the needs of organic and reduced-input systems. Among emerging nonchemical technologies, electrical weed control (EWC) is receiving increasing attention as a tool capable of targeting both annual and perennial weeds.

Since 2021, weed scientists at UC Davis, Oregon State, and Cornell, supported primarily by a USDA-OREI grant, have evaluated EWC in perennial crops using commercial Zasso Group units (Figure 1). These units convert engine power into high-voltage electricity, which is delivered through flexible metal electrodes that sweep across vegetation beneath the canopy. The electric current heats plant tissues and disrupts cellular structure, ultimately causing wilting and death. EWC performance varies with plant characteristics, soil conditions (such as moisture and texture), and operational settings, including energy dose, travel speed, and number of passes. The goal of this research was to determine how these biological and operational factors influence control and to identify combinations that deliver consistent, effective results across diverse field environments.

Oregon trials

A coordinated field–greenhouse study targeting yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) demonstrated that EWC can suppress shoot emergence and, when optimally delivered, weaken tuber viability. Slow travel speeds (0.5 kilometers per hour, delivering approximately 144 kilojoules per square meter) resulted in strong early-season nutsedge suppression. However, the longest-lasting control, up to 80 days after treatment, was achieved when mowing was followed by EWC in a sequential program. Across locations, the combination of mowing with EWC consistently outperformed either tactic alone, reducing nutsedge shoot emergence in greenhouse assays and lowering tuber density in the field. Notably, treatment order mattered: mowing followed by EWC gave substantially better control than the reverse sequence. These results highlight that EWC is most effective when integrated into a multi-step program that weakens top growth before targeting underground propagules.

Complementary research in organic highbush blueberry systems examined how vehicle speed and number of passes shape EWC outcomes. Slower speeds (0.5–1 kilometers per hour) delivered higher energy per unit area and consistently produced more than 80% control at 28 days after treatment. However, repeated treatments were required to manage regrowth, particularly for perennial grasses and low-growing creeping species. In some cases, two moderately fast passes matched the results of a single slow pass, offering potential efficiency gains. Species-specific responses were clear: upright broadleaf weeds were highly susceptible to EWC, while perennial grasses required repeated, higher-energy applications. These findings reinforce the importance of tailoring EWC scheduling to species biology and landscape context and support its integration with complementary practices such as mowing.

California trials

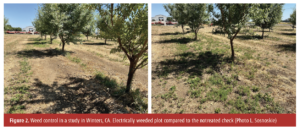

A multiyear trial in a young, organic almond orchard near Winters, California, dominated by yellow nutsedge, annual grasses and field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis), evaluated EWC performance in response to unit power settings, number of passes and ground speeds. A mowing treatment was also included as a standard of comparison. The most and least energy-intensive EWC programs reduced weed cover to less than 5% and 10%, respectively, at 14 days after treatment. By contrast, weed cover in the mowing treatments averaged 40%. At 30 days after treatment, weed cover in the most energy-intensive treatments remained under 20%, despite drip irrigation, which can promote weed regrowth (Figure 2). No negative effects on tree growth were detected for any treatment. Soil health indicators, including respiration and biological activity, were similar between EWC and mowing treatments, suggesting that electrical applications did not disrupt soil function.

Fire risk is a major concern in California. During hot, dry periods, electrical arcing can ignite plant debris, especially at the boundary between the EWC-treated strip and the mowed interrow where residue accumulates. Using higher power settings can further increase this ignition risk. Scheduling applications shortly after irrigation can help reduce fire hazards by improving soil conductivity, although treatments should not occur immediately after watering. Saturated soils draw excessive power, which may exceed the horsepower capacity of smaller tractors. As a result, careful monitoring of soil moisture is essential for both safety and performance.

New York trials

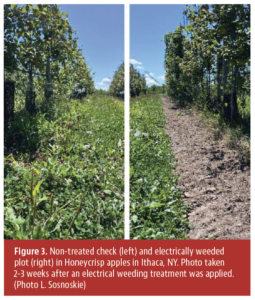

In New York, trials were conducted in newly planted and mature organic apple orchards in Geneva and Ithaca. Across locations, EWC consistently matched or exceeded the performance of other organic practices, including wood chip mulch, organic herbicides and cultivation. For instance, three EWC passes, applied once each in June, July and August, reduced end-of-season weed cover to less than 10% in the mature orchards (Figure 3). In comparison, cultivation resulted in 15% to 45% weed cover, and untreated plots maintained 60% to 75% cover.

No negative effects on tree growth or canopy development were observed. In fact, plots without weed control showed the most significant setbacks. In the newly planted orchard study, trunk diameters in treated plots increased by 20% to 40% over the season, while trees in untreated plots showed no measurable growth. These results highlight the agronomic cost of unmanaged weed competition in young orchards.

Cover crops

Effective, nonchemical termination is especially critical in organic no-till systems, which require complete cover crop kill before planting to prevent regrowth and competition. In Oregon trials, EWC demonstrated strong potential as a termination tool, though performance varied by species (Figure 4). For example, while EWC and mowing were equally effective at terminating crimson clover, mowing provided only 20% oat control. EWC increased oat control to around 80%. Mowing followed by EWC increased control to more than 90%.

Cover crop biomass and plant moisture were key factors influencing EWC performance and safety. In dense stands, lower canopy material sometimes escaped direct electrode contact, reducing termination success. Conversely, dry biomass increased ignition risk. Fire hazard was noticeably lower during early morning applications, when dew was present and winds were calmer. Overall, these findings demonstrate that EWC can be an effective tool for cover crop termination and may broaden its role in annual production systems.

Summary

Weed pressure in perennial systems threatens yield, quality and long-term orchard and vineyard productivity. Herbicide-only strategies are increasingly constrained by resistance, regulation and inconsistent performance. Electrical weed control is emerging as a viable nonchemical alternative. Multistate research shows that EWC can match or exceed mowing, cultivation, mulching and organic herbicides for weed suppression. Integrating EWC into diverse weed control programs may be more effective than relying on it as a sole tactic. Early results suggest that EWC does not negatively affect tree growth or soil biological activity. However, safety considerations, especially fire risk under hot, dry conditions, must be accounted for during scheduling and operation. Trials also show strong potential for EWC in cover crop termination, broadening its usefulness in organic and reduced-input systems.