Black-eyed peas, also called cowpeas, are a bean species native to Africa in the Vigna genus of legumes. Cowpeas were introduced to the United States as early as the 16th century by Spanish colonists and through the trans-Atlantic slave trade. “Blackeyes,” as they’re called locally, are grown by California growers on approximately 8,000 acres each year to produce a nutrient-rich food for consumers. Most production in California goes to the dry bean sector for canning and bagging. A small amount of the crop is produced for fresh consumption, similar to green beans or snap peas, and may be sold at farmers markets.

Blackeyes are an important crop in the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys, where diverse crop rotations are common. A relatively drought-tolerant crop, blackeyes are usually flood or furrow irrigated. Growers rarely fertilize with nitrogen since blackeyes efficiently fix nitrogen from the air due to the plant’s symbiotic relationship with a root-inhabiting Rhizobia bacteria species. Additionally, blackeyes are moderately tolerant of salinity and can grow in conditions where yield declines would be expected for other summer annuals like corn and tomatoes. These characteristics of blackeyes can be an economic incentive to grow them in some years and will be important in California, particularly under hotter and drier conditions expected with climate change.

Plant Breeding for the Future

As California shifts toward drier and more extreme weather, blackeyes, like most cultivated plants, will experience new pressures that growers will be first to manage. Heat stress and drought vulnerability, emerging and invasive insect pests, increased weed competition and the evolution of endemic and invasive diseases are some of these pressures. Plant breeding that considers these stresses will help the industry stay ahead of the curve.

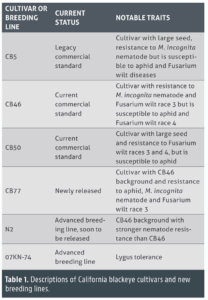

UC has a long history of variety development for the California blackeye and garbanzo industries. For blackeyes, the current standard varieties are CB46 and CB50, which were released in 1990 and 2009, respectively. CB46 is high-yielding and has Fusarium wilt race 3 resistance, but it is susceptible to virulent and aggressive races of root-knot nematodes, Fusarium wilt race 4, aphids, lygus and late-season diseases known collectively as ‘early cut-out.’ Additionally, the market now prefers larger seed and whiter grain than what CB46 provides. CB50 is high-yielding, has larger seed size than CB46 and is resistant to Fusarium wilt races 3 and 4 and root-knot nematodes.

To support plant breeding efforts, new breeding lines and cultivars are trialed at research facilities and then on commercial farms to evaluate material across environmental conditions. New materials are evaluated against commercial standards for yield, quality and pest resistance. The cultivars and advanced lines that have been trialed across regions and years are described in Table 1. UCCE farm advisors have collaborated for more than 10 years with UC Riverside plant breeders to test improved lines and, over the last five years, have conducted 21 trials across seven locations in the Central Valley.

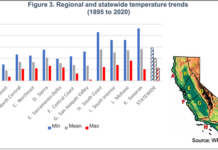

The variability in precipitation and average air temperature down the Central Valley can influence blackeye phenotypic traits. For example, in Five Points (southern San Joaquin Valley) from 2020 to 2025, the mean annual precipitation was 7.6 inches, whereas Davis (southern Sacramento Valley) had a mean annual precipitation of 17.1 inches. Similarly, average daily air temperature in June, July, August and September over the same five-year period in Five Points was 78 degrees F but was 73 degrees F in Davis. It is important to test experimental lines across regions to understand how they will perform in different environments.

California growers who serve on the California Dry Bean Advisory Board have identified high yield, seed quality and disease resistance as top priorities for plant breeding efforts. They have also emphasized the importance of regional acclimation. The following are some highlights from research funded by the California Dry Bean Advisory Board, USAID Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Legume Systems Research and California Crop Improvement Association, made possible through the generous support of numerous growers, bean harvesters and bean handlers.

Regional Trial Results

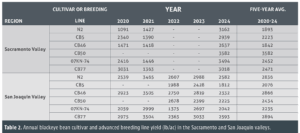

Yield results from 2020 to 2024 trials are summarized for the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys (Table 2), where average yields ranged from 1,091 to 3,582 pounds per acre. The lowest yield occurred in 2020 and the highest in 2024, both in the Sacramento Valley. Interestingly, yields in the San Joaquin Valley were 27% lower than in the Sacramento Valley in 2024. While yields are usually higher in the San Joaquin Valley, the lower yields may have resulted from a prolonged heat wave and above-average nighttime temperatures, which caused significant crop losses.

Seed size is an important quality factor in blackeye production related to consumer preferences. Average seed size, reported as the weight of 100 seeds, for the last five years of trials is shown in Table 3. Seed size ranged from 20.0 grams per 100 seeds for CB77 (2020, Sacramento Valley) to 27.8 grams for CB50 (2024, Sacramento Valley). CB5 and CB50 consistently have the largest seed size across sites from year to year, while the experimental lines tend to have smaller seed size, similar to CB46 and CB77. Over the last five years, average seed size in the San Joaquin Valley was approximately 7% smaller than in the Sacramento Valley.

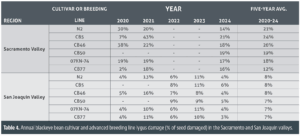

An important insect pest of blackeyes is lygus, which kills fruits before they develop, resulting in direct yield loss. Lygus feeding, called “stings,” also damages and discolors seeds after pods develop (Fig. 1), which reduces yield and diminishes the quality of the beans. The results for lygus damage, shown as the percent of seed with lygus stings, are shown in Table 4. The average lygus damage ranged from 2% for CB77 (2020, Sacramento Valley) to 43% for CB5 (2021, Sacramento Valley). Average lygus damage in the Sacramento Valley over the last five years was 20%, while in the San Joaquin Valley it was 7%. Importantly, under the heavy lygus pressure in the Sacramento Valley, the five-year average lygus damage was lower for experimental line 07KN-74 and newly released CB77 compared to the commercial cultivars CB5 and CB46. This demonstrates a high yield potential and reduced need for insecticides to control lygus with the newer material. With little development of new insecticides for use in dry beans, the importance of insect-resistant varieties cannot be overstated.

New material is also evaluated for disease resistance (data not shown). The evolution of Fusarium wilt provides an example of why plant breeding is critical to disease management. CB5 is an older blackeye variety that is susceptible to Fusarium wilt race 3. CB46 was released as a commercial variety with Fusarium wilt race 3 resistance. However, after years of production, CB46 started showing susceptibility to Fusarium wilt race 4. CB50 was then introduced as a new variety with resistance to both Fusarium wilt race 3 and race 4. During trialing, advanced breeding lines are grown alongside traditional cultivars (like CB5, CB46 and CB50) to quantify how new material compares to varieties already on the market. Lines are evaluated over multiple years to capture variability in pest pressure, weather and other yield-limiting conditions.

Research Outcomes

Recently developed varieties show resistance to disease and aphids, while new breeding lines show great promise for nematode or lygus resistance. Recently, CB77 was publicly released as an improved variety with similar yield and quality to CB46 but with resistance to cowpea aphid (Fig. 2). It also has a brighter white color than CB46 (Fig. 3). The California Crop Improvement Association currently holds foundation seed of CB77 and will distribute it to growers who successfully apply to grow certified seed for commercial production.

Lines N2 and 07KN-74 will be ready for public release within a year. Line N2 is a root-knot nematode-resistant line with high yields in the San Joaquin Valley. Root-knot nematodes damage roots, which diminishes water uptake and yield. As fumigants are phased out through regulatory processes, host resistance and alternative strategies for reducing root-knot nematode damage must be taken into consideration. Line 07KN-74 is a lygus-tolerant variety with moderate yield, similar to or slightly lower than the commercial standard CB46. This article summarizes the plant breeding and trialing efforts to improve blackeyes for the California industry. Yield, quality and pest resistance are important traits for plant breeding efforts, and this article summarizes years of data across multiple locations in the Central Valley. These evaluations are ongoing and provide growers with first-hand information on how new genetic material performs under commercial farming conditions. Growers who are interested in learning more or hosting on-farm trials should contact the authors, who would be glad to help make those arrangements.