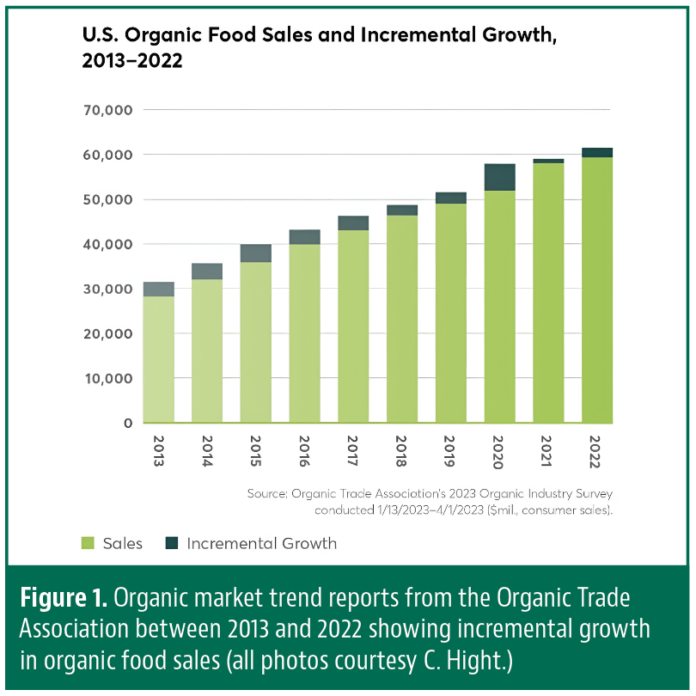

The first concepts of organic agriculture as we now know it were developed in the early 1900s by Sir Albert Howard, Rudolf Steiner and F. H. King (Adamchak 2024). These individuals believed in the use of animal manures, composts, cover crops, crop rotation and a very early version of integrated pest management that, when combined, resulted in a better system approach to farming. After World War II and the invention of the Haber-Bosch process, there was an excess of nitrogen-containing compounds, and to relieve the excess, these products were applied to agricultural fields. While yields increased, there was an unforeseen detriment to natural populations of microbes and beneficial predators. Modern organic farming developed as a response to the environmental harm of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers used in conventional agricultural systems. Organic farming has been shown to lower pesticide usage, reduce soil erosion, increase cycling of nutrients (which decreases the likelihood of leaching to groundwater and surface water) and aid in recycling animal wastes. Although more ecologically friendly, organic farming tends to have a higher production cost and generally a lower yield. With an increasing concern for pesticide residues and consumer awareness of genetically modified organisms, organic food sales have steadily increased over the latter half of the 20th century and continue to show increases today (Fig. 1).

Organic Vegetable Production Practices

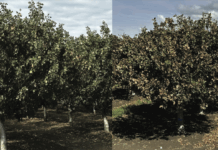

Organic vegetable production systems rely on natural inputs, such as amino acids, proteins, composts and manures, to supply nutrients to the plants. These N-containing inputs must go through the process of mineralization from amino acids to ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3–) by microorganisms to become plant-available. The availability of nutrients supplied to the plants depends on many factors, such as carbon to nitrogen ratio and N% of the material as well as the moisture, temperature and texture of the soil. The release of N from these materials is variable but predictable in a laboratory setting, however in-field factors make release timing and quantity difficult to anticipate (Lazicki et al. 2020). This can lead to lower crop yields and difficulty controlling pests (Giampieri et al. 2022). An increased reliance on a whole systems approach is needed to effectively produce organic vegetables. There is evidence to suggest practices, such as legume cover crops and reducing tillage, can increase soil organic matter (SOM) and provide additional nutrients in both organic and conventional systems (Fig. 2). Growers who grow organically can expect a higher input cost but can typically also expect a higher price at the market. Consumers who purchase organic produce view this as a way to consume less synthetic pesticides and increased nutrient content (dos Santos et al. 2019). Organic inputs also provide a higher amount of C to the soil, increasing microbial biomass and activity, which are seen as positive soil health indicators. Published reports show under organic management, total and organic C, total N, available phosphorus and calcium, magnesium, manganese, zinc and copper were greater compared to conventional systems (Chausali and Saxena 2021). The dynamics of N mineralization (Nmin) may also be affected by long-term organic management compared to conventional management. Once again, a whole systems approach to organic farming is necessary to reap high yields with low pest pressure and a low environmental impact.

Conventional Vegetable Production Practices

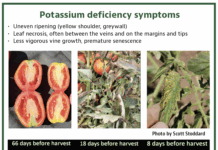

Conventional vegetable production systems rely on synthetic fertilizer and pesticides to provide nutrients to plants and protect them from disease and insects. While synthetic fertilizer inputs can target key growth points to maximize yield and reduce environmental pollution, synthetic fertilizers can be detrimental to natural soil microbial populations. Additionally, caution must be taken as overapplying N- and P-containing fertilizers can move with soil colloids and surface water to pollute rivers and streams. Consumers see synthetic pesticides with a negative connotation but may not understand the precision, regulation and care with which the synthetics are applied (Fig. 3). Improper use of insecticides, fungicides and other pesticides can cause insects and other pests to develop resistance to chemistry within said formulations. These same synthetics may reduce microbial populations, leading to decreased overall soil health. However, when managed correctly, these products can rescue crops from infestations of insects or other diseases. Conventional production provides growers more room for error as many products can provide nutrients immediately compared to organic systems that require mineralization of nutrients to become available to plants. Additionally, with a well-timed pesticide application, potential crop loss due to an insect swarm can be mitigated, often easier said than done in organic production. While all farming is difficult, conventional farming is more forgiving than organic farming on individuals learning the art of vegetable production.

Comparing the Two Paradigms

On California’s Central Coast, a study is currently underway investigating Nmin dynamics of 20 pairs of organic and conventional fields with similar environmental conditions and soil types. After a vegetable crop is harvested, 6-inch undisturbed soil cores are taken alongside a composite 6-inch soil sample (Fig. 4). The soil sample represents the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of the soil pre-incubation. The undisturbed cores are then incubated for 10 weeks at 25 degrees C and 60% water holding capacity to determine how much N mineralizes or immobilizes within that period. The entirety of the samples will be analyzed as such, and analyses will be performed to determine the most significant characteristics driving N availability. We hypothesize the organic fields will have a lower starting inorganic N content but mineralize more N over a 10-week incubation, and characteristics that most impact the quantity mineralized will be water holding capacity, SOM content and N% in the soil.

Is a Combination of Practices Best?

Conventional and organic management systems produce many of the same vegetables on the Central Coast, including broccoli, cauliflower, romaine and celery. Similar nutrient requirements are needed to produce adequate yields in both systems. Conventional systems provide inorganic nutrients that are immediately available for uptake bypassing the need for microbial mineralization. N-containing organic amendments require microbial decomposition to become available to plants. N dynamics in either system depend on a multitude of factors, including other cations and anions, SOM content, N% of the soil, moisture and temperature of the soil as well as amendments and crop residues added. While conventional practices allow for immediate applications of fertilizers and pesticides and organic fields require a whole systems approach and forward thinking, potentially bridging the gap between the two practices could be a practical approach. The added organic amendments with their high carbon content can contribute to soil health metrics and a robust microbial population, meanwhile the grower knows they have a failsafe in the back pocket in case something goes wrong. This lends to sustainable agriculture, which strives to provide resources necessary for our population to thrive while also conserving the planet’s natural ability to sustain future populations of plants, animals and humans. All this to say the preference for organic vs conventionally produced vegetables is for the consumer to decide. The practices that promote the best soil, air and water will be determined by a combination of growers and researchers interacting with and weighing practicality, sustainability and return on investment.

References

Adamchak, R. (Dec. 21st, 2024). Organic Farming. In Biritannica (Ed.), Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/organic-farming.

Chausali, N., & Saxena, J. (2021). Chapter 15 – Conventional versus organic farming: Nutrient status. In V. S. Meena, S. K. Meena, A. Rakshit, J. Stanley, & C. Srinivasarao (Eds.), Advances in Organic Farming (pp. 241-254). Woodhead Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822358-1.00003-1

dos Santos, A. M. P., Lima, J. S., dos Santos, I. F., Silva, E. F. R., de Santana, F. A., de Araujo, D. G. G. R., & dos Santos, L. O. (2019). Mineral and centesimal composition evaluation of conventional and organic cultivars sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam) using chemometric tools. Food Chemistry, 273, 166-171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.12.063

Giampieri, F., Mazzoni, L., Cianciosi, D., Alvarez-Suarez, J. M., Regolo, L., Sánchez-González, C., Capocasa, F., Xiao, J., Mezzetti, B., & Battino, M. (2022). Organic vs conventional plant-based foods: A review. Food Chemistry, 383, 132352. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132352

Lazicki, P., Geisseler, D., & Lloyd, M. (2020). Nitrogen mineralization from organic amendments is variable but predictable. Journal of Environmental Quality, 49(2), 483-495. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20030