Pistachio has enjoyed decades of limited reported damage from plant-parasitic nematodes. This contrasts with other tree nut crops as almond and walnut. While almond and stone fruits were long encumbered by root-knot nematodes, these crops have benefitted from protection against these culprits by the introduction of peach rootstock ‘Nemaguard.’ This fascinating rootstock carries sustainable resistance since the 1960s. Only more recently has the detection of the peach root-knot nematode (PRKN) illustrated the vulnerability of this and other rootstocks with resistance to southern root-knot nematodes other root-knot nematode species. The distribution of PRKN is not documented yet. Both walnut and almond are efficient hosts of the walnut root lesion nematode (RLN). These crops have long-term challenges with RLN, especially its primary host walnut that gets damaged by only one nematode per 250 cc of soil. No sustainable resistance and tolerance to RLN is currently commercially available in rootstocks of these crops.

The interaction of plant-parasitic nematodes and their hosts is two-fold. The one component is the response to nematode infection; some genotypes respond with no damage independent of the nematode reproductive potential on their roots (i.e., they are tolerant). Others may get hurt from only a few nematodes (i.e., they are sensitive/intolerant). As the second response, the roots may allow for nematode reproduction (susceptible) or they may prevent such (resistant). Both parameters are very important for the field performance of plants. Genotypes that are resistant but sensitive will cause tolerance without any resistance and can lead to build-up of nematode population densities that may cause problems for the following plantings.

Pistachio seemed free from these issues, likely based on a 1980s survey where no typical plant-parasitic nematodes at meaningful numbers were found on pistachio roots. In those days, the developing pistachio industry frequently used Pistacia atlantica as rootstock for the nut cultivars. Genotypes of this species were known to be on average resistant to RLN. In fact, some researchers used it as a resistant standard in their resistance determining studies. Growing P. atlantica rootstocks may have protected plantings from nematode infections.

While such rootstocks were useful regarding plant-parasitic nematodes, they were highly susceptible to Verticillium dahliae, the causal agent of Verticillium wilt that threatened the industry in the late 1980s. This crisis required major changes in the management of pistachio. While some optimization in cultivation of the crop could mitigate severe damage, ultimately, plants were required that would not be impacted by this soil-borne disease. Crosses of Pistacia atlantica and P. integerrima were identified as being resistant to Verticillium wilt.

Some hybrid rootstocks were used as seedlings (e.g., PG II or UCB1), but with the capacity of clonally propagating the genotypes in tissue culture, clonal rootstocks became more abundant. The name UCB1 is used for any clones out of that specific directed cross. Yet, there are distinct differences among UCB1 rootstocks. This is indicated by some nurseries by providing additional identification of specific clones. With this change in rootstocks, the genetic protection from plant-parasitic nematodes may be obsolete. In fact, screens of experimental UCB1 clones conducted by Dr. M. McKenry illustrated large variability of nematode susceptibility. In more recent screens with the most widespread nematode species at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center (KARE), susceptibility of different UCB1 clones was confirmed under field conditions.

In addition to the changes in rootstock genetics, pistachio is now frequently planted to fields that were used for the production of other perennial crops hosting plant-parasitic nematodes. In screens of pistachio, limited susceptibility to root-knot nematodes, nematodes feared after grape or cotton, was ascertained. In contrast, susceptibility to RLN was on a similarly high level as under other known tree nut crops. The build-up of these populations took long, but the principal susceptibility was confirmed. Such finding creates the potential challenge when pistachio is planted after almond and in particular after walnut. The latter crop is going through a phase of ample removal because of water restrictions, fumigant restrictions, and poor market conditions. Walnut rootstocks liable to have been used for decade-old walnut orchards are notoriously leaving behind concerning RLN population densities. This creates a potential risk for planting pistachio.

Current Threat of Root Lesion Nematode

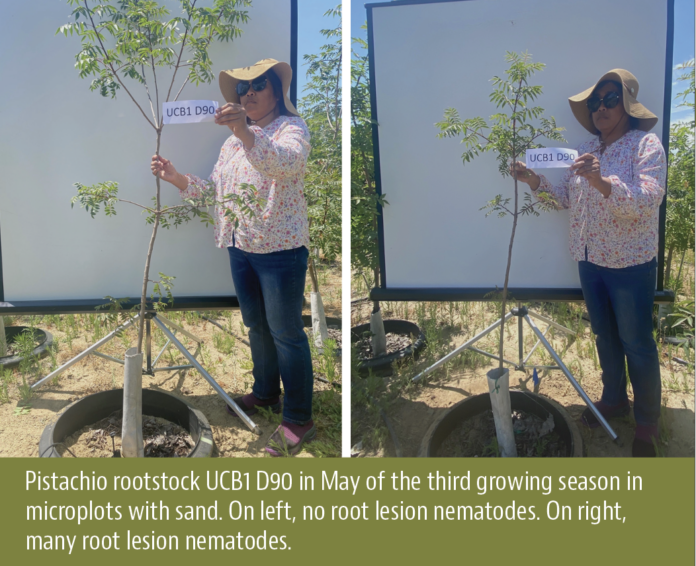

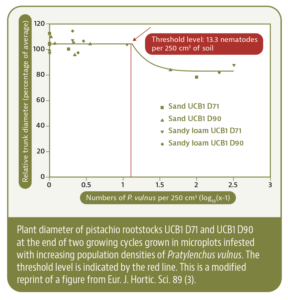

Considering this background information, the question remains: How damaging is RLN to today’s pistachio plantings? The classical way to examine the damage potential of a plant-parasitic nematode on a specific crop is to expose the plant to increasing levels of the target nematode and measure growth response of the plants. In microplot experiments at KARE, such differing population densities were created by fractional fumigation that left behind varying population densities of RLN. Such plots were then planted to two different UCB1 clones that had tentatively shown different susceptibilities to RLN, and different overall vigor.

These trees were grown for two years. At the end of the second year, plant growth was measured and related to the initial population densities of RLN. With higher numbers of RLN, plants were weaker at this evaluation time, this was proportionally true for both rootstocks. In statistical analysis with the so-called “Seinhorst function,” the threshold level was determined where nematode numbers started causing damage to the trees. This level was around 13.3 vermiform nematodes per 250 cc of soil. Similar confirmatory results were found in a second microplot experiment (a more technical report of this study can be accessed at pubhort.org/ejhs/ahi/1420/1420.pdf.)

Such population densities can be frequently found after a walnut orchard. So, care needs to be taken when pistachio follows walnut. Similar numbers can also be found after almond. Sampling is mandatory when replacing a tree nut crop with another. RLN infects the nut crops and the presumed benefits of “crop rotation,” or better crop change, do not encompass this nematode pest. It infects all three nut crops with differing damage potential. The recommendation is to sample fields for nematode detection holds (more soil sampling information and tips are found at youtube.com/watch?v=U7x0xHoKqC8.)

When diagnosing nematode problems in the field, those may often be overlooked. Pistachio orchards are cultivated under a rigorous pruning and training regimen. Some of the variability from tree-to-tree that would be a typical first indication of tree health issues may go unnoticed because of that. In addition, other soil differences may overlay areas where nematode infections are damaging and may lead to unwarranted conclusion of their responsibility for the differences detected. To bring more clarity to this topic, more field work is necessary. Especially the threshold level experiments require confirmation under commercial conditions. If readers were interested in participating in such studies, they are encouraged to reach out to the author Dr. Andreas Westphal at andreas.westphal@ucr.edu or 559-646-6555 to learn more on what is involved in such studies.

In summary, pistachio is not home-free from the risk for nematode damage. Vigilance and care need to be exercised when planning a new orchard planting. Soil sampling for nematode detection should be an instrumental procedure in this process.