Roundup Ready technology builds genetic resistance to glyphosate into crops, providing an excellent tool for weed management. Initial screening in the early 2000s found good crop safety in alfalfa, leading many growers to rely on glyphosate as the only herbicide. Although using the same chemical control season after season is not a good idea because it may accelerate herbicide resistance in weeds, Roundup Ready alfalfa has been successfully used with few to no concerns. However, the combination of glyphosate and cold weather may cause crop injury, especially in regions where frost events typically follow the herbicide application in spring.

It All Started in Siskiyou County

The issue was first observed in 2014 by Steve Orloff, former UCCE farm advisor in Siskiyou County. A Roundup Ready alfalfa field showed injury after glyphosate application followed by freezing temperatures. The main symptoms were plant stunting, chlorosis and “shepherd’s crook,” in which individual alfalfa stems curl over and die (Figure 1). Yield reductions were also observed for the first cutting. Steve noticed the injury could be related to the glyphosate application because a section of the field where an irrigation wheel line prevented the herbicide application looked perfectly normal.

Injury Symptoms Were Like a Known Disease

Interestingly, the injury seen was very similar to symptoms caused by frost and/or bacterial stem blight (BSB) caused by Pseudomona syringae, a waterborne bacteria present everywhere. The bacteria can exacerbate frost damage due to its protein that mimics a crystalline structure and provides a starting point for ice formation, damaging the plant tissue and serving as an entrance port into the leaves and stems. Once into the plant tissue, colonization leads to infection and symptoms about 7 to 10 days after the frost event. Symptoms on stems start as water-soaked lesions that extend down one side. Leaves become water-soaked and often are twisted and deformed. Currently, there are no resistant alfalfa varieties nor effective control methods besides harvesting the crop earlier.

Let the Research Begin

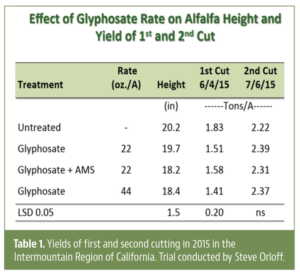

Steve replicated the symptoms in field trials conducted in 2015-17. The field trials showed yield reductions of up to 0.7 tons/acre in the first cutting in Scott Valley. Crop injury was not observed in a similar field trial conducted in 2014, probably because there was no frost event after the glyphosate application. Similar impacts were observed in a trial at the UC Intermountain Research and Extension Center, near Tulelake, Calif.; additional yield reductions were observed with higher glyphosate rates (Table 1).

Broadening the Scope of the Research

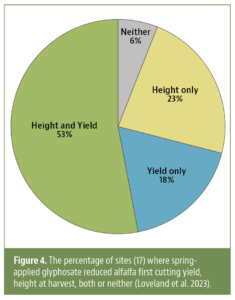

Based on this work, a multi-year project started to investigate the effects of glyphosate rate and application timing at 24 sites over five years, measuring the impact on alfalfa crop height and biomass yield. Results were published in the Agronomy Journal in 2023 (Loveland et al. 2023). All locations in this study were in the Intermountain West (California and Utah), and results showed while summer glyphosate application did not injure alfalfa, spring applications reduced crop height at 76% of the sites and biomass at 62% of the sites.

In sites where glyphosate application resulted in crop injury, low (22 oz/acre) and high (44 oz/acre) rates of glyphosate reduced yields by 0.24 tons/acre and 0.47 tons/acre, respectively (Figure 2).

Data also showed the crop height at glyphosate application influenced the degree of injury (Figure 3), with greater yield reductions at 30 to 40 cm (12 to 16 in) than at 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 in).

Do Alfalfa Growers Need to Panic?

As alarming as the possibility of injury might sound, its occurrence and degree are widely variable, and the crop resumes normal growth and yields after first cutting. Figure 4 illustrates this complexity and variability throughout experimental sites where harvest yield and crop height were assessed. Note the locations represented in the following graph are colder than the San Joaquin Valley and the injury happened after glyphosate applications in spring.

As of 2024, this type of injury has mostly been reported in the Intermountain West due to its high altitude and cooler weather. However, one field I visited in early February 2024 in Firebaugh, Calif. brought my attention back to the issue. The field was planted in fall 2023 and had many of the symptoms previously mentioned: plant stunting, typical shepherd’s crook, chlorosis and dead stems. While all these symptoms could be exclusively due to bacterial blight infections or frost, parts of the field where glyphosate application was accidentally skipped looked better.

Considerations and Recommendations

The exact role of glyphosate, temperature, and P. syringae in the injury is unclear. Although most of the sites in this research showed some level of injury followed by glyphosate application in the spring, the degree of the damage was widely variable. Interestingly, injury symptoms worsened with increasing glyphosate rate and crop height up to when alfalfa was 8 inches tall, but the crop somehow seemed less susceptible when glyphosate was applied at 8 to 16 inches tall.

While the initial cases of BSB of alfalfa were reported in 1904 in Colorado, relatively few cases were reported during the second half of the 20th century. However, the disease has become increasingly problematic in past decades, especially in areas where frost events are favorable. Would the re-emerging BSB in alfalfa have something to do with the extensive use of Roundup Ready technology and the overreliance on glyphosate? Future research is needed to answer this question.

Current UC IPM weed management guidelines for Roundup Ready alfalfa recommend rotating herbicides with different modes of action to reduce the development of herbicide-resistant weeds and avoid glyphosate overuse during the colder winter months. Second, spray glyphosate when the alfalfa is short (<2 in) when using the higher rate (44 oz/acre) or 4 inches when spraying at the lower rate (22 oz/acre). Third, use the lowest glyphosate rate possible according to the weeds present and their stage of development; a soil residual herbicide tank mixed with early glyphosate application should provide adequate late-emerged weed control. Finally, pay attention to the weather forecast; applying glyphosate before frost events increases the likelihood of crop injury, especially in old stands.

References

Loveland, L.C., Orloff, S.B., Yost, M.A., Bohle, M., Galdi, G.C., Getts, T., Putnam, D.H., Ransom, C.V., Samac, D. A., Wilson, R., and Creech, J E. (2023). Glyphosate-resistant alfalfa can exhibit injury after glyphosate application in the Intermountain West. Agronomy Journal, 115, 1827-1841. https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.21352