Proper nutrition management allows vines to grow healthy canopies and produce fruit with desirable quality. Fertilization is used to correct nutrient deficiency and improve vine productivity. Even in vines without foliar symptoms, growers may fertilize as a routine practice to compensate nutrient loss at harvest and prevent nutrient deficiency. As a result, sometimes managing vine nutrition simply means applying fertilizers. I would argue that understanding vine nutrient status and determining their nutrient needs are as important as fertilization itself.

Grapevines have lower fertilization requirements than many agricultural crops.

Overfertilization does not offer many benefits from economic or vine productivity points of view. Instead, it could compromise vine balance, decrease fruit quality and negatively affect the environment. Let’s use nitrogen (N) as an example here. Excessive N additions lead to jungle-like canopy with limited light penetration and air circulation, increase disease pressure and negatively affect fruit quality. Excessive amounts of nitrate in the soil also increase the risk of groundwater and surface water contamination.

Supplying vines with ample but not excessive nutrients is easier said than done. In this article, I will start the story with summarizing previous work on whole vine nutrient budget and then extend the discussion to determining vine nutrient requirements and fertilization.

Whole Vine Nutrient Budget

Studies were conducted under field conditions in California and Oregon and in potted systems in South Africa to track nutrient uptake, movement and distribution among vine organs at different phenological stages.

In terms of macronutrients, annual growth is a strong sink for N, phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) between bud break and veraison. Required nutrients of shoots, leaves and clusters can be obtained from two pools: nutrients remobilized from permanent organs and those taken from soil. In mature vines, up to 50% of N and P in new growth can be supplied by the stored reserve in trunks and roots. On the other hand, less than 15% of K, Ca and Mg are remobilized from the reserve, since only a small percentage of those nutrients can be recycled during leaf fall. Clearly, nutrients obtained from the soil still account for a large portion of required nutrients, even in the mature vines. Young vines have less nutrient reserve than older vines, and thus rely more on nutrients supplied by root systems. Nitrogen uptake peaks between bud break and bloom, while uptake of other macronutrients usually reach the max between bloom and veraison. Nutrient uptake also takes place after harvest when nutrients are available in the soil and weather conditions are favorable.

The uptake and distribution of micronutrients is less understood as compared to macronutrients. Dr. Paul Schreiner, scientist at USDA-ARS, studies the budget of micronutrient in young and older ‘Pinot noir’ vines in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. In young vines, boron, zinc, manganese and copper were taken between bud break and harvest, with the peak of uptake occurring between bloom and veraison. The uptake and allocation of micronutrients appears less consistent in mature vines.

Please note that research findings reflect vine nutrient budget under specific conditions and should be interpreted with caution. Factors like soil nutrient availability, irrigation practices, rootstock and scion combination and weather conditions have large impacts on nutrient uptake and allocation. Clearly, vine nutrient demand varies between vineyards. So, how should one determine whether fertilization is needed at a specific site?

Determine Nutrient Requirement of Vines

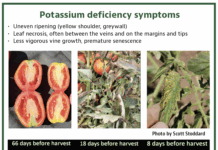

Nutrient analyses of leaf blades and leaf petioles at bloom and veraison are indicators of vine nutrient status. Many testing labs provide the comparison of leaf nutrient concentration to the normal range for each nutrient.

We recommend growers not relying solely on numbers on lab results to make fertilization decisions. First, variability in vine nutrient requirement is expected between vineyards and across seasons. Even if the tissue nutrient concentration of a vineyard is slightly below the given normal range, it does not mean vines surely experience nutrient deficiency. Second, normal ranges of leaf nutrients are estimated in experiments where vines received a specific nutrient at different rates and had its concentration over a wide range of leaf tissues. Given the difference in experimental setup, the normal range determined can vary between studies. Thus, the normal range for nutrients should be used only as references when it comes to interpreting vine nutrient requirements. Historical nutrient data, vine growth and production goals are important to consider. For example, fast-growing canopies may have lower leaf N concentration, especially in newly expanded leaves, but does not mean that vines require N fertilization. Instead, rapid shoot growth often indicates ample N and water availability in the soil.

Fertilization

In vineyards where fertilization is needed, growers and CCAs often ask me about the amount, formula and application timing of fertilizer. Rather than providing generalized answers for those questions, I would like to share some tips. Please feel free to reach out for questions related to your vineyards.

About 3 lb N, 0.5 lb P and 5 lb K are removed from a vineyard with each ton of harvested fruit. Many would use those numbers to calculate how much fertilizer is needed to compensate the loss during harvest. In reality, supplementing vines only with nutrients removed from the vineyard may not be sufficient. For instance, data from western Oregon showed that young ‘Pinot noir’ vines acquired 12.5 lb N, 3 lb P and 25 lb K per acre via uptake with the crop level at 2.0 ton/acre.

Compost is an affordable, slow-releasing fertilizer. Applying compost in the spring supplements vines with nutrients, boost soil microbial activity, improves soil water penetration by aggregation and enhances water holding capacity. Increasing soil organic matter is good practice for soil health in general.

Soil pH plays key roles on nutrient availability. Most nutrients become more available in soils with neutral pH. Regular soil sampling and testing can help with managing and adjusting soil pH if needed.

If nutrient deficiency is observed late in the season, immediate fertilization may not alleviate the symptoms. It is because the period when nutrient deficiency becomes evident would not be coincident with the period when nutrient uptake peaks. Making applications at the right timing in the following season may be more effective on correcting deficiency.

Even though vines obtain nutrients mainly from the soil by roots, foliar application can be an additional tool to supplement vines with nutrients. In the past, we successfully increased fruit N at harvest in wine grapes by applying urea to foliage between fruit set and veraison. Foliar application of P and Mg was found to reduce leaf symptoms in wine grapes. Some PCAs suggest foliar Ca and Mg sprays between bloom and veraison can increase berry firmness and reduce powdery mildew occurrence in table grapes.

Applying fertilizers in small doses may improve fertilization efficiency in vineyards with shallow root systems. Theoretically, frequent fertilization with lower doses allows roots to better catch nutrients and reduce leaching.

References

Araujo FJ and Williams LE. 1988. Dry matter and nitrogen partitioning and root growth of young field-grown Thompson Seedless grapevines. Vitis 27:21-32.

Conradie WJ. 1980. Seasonal uptake of nutrients by Chenin blanc in sand culture: I. Nitrogen. S Afr J Enol Vitic 1:59-65.

Conradie WJ. 1981. Seasonal uptake of nutrients by Chenin blanc in sand culture: II. Phosphorus, potassium, calcium and magnesium. S Afr J Enol Vitic 2:7-14.

Schreiner RP, Scagel CF and Baham J. 2006. Nutrient uptake and distribution in a mature ‘Pinot noir’ vineyard. HortScience 41:336-345

Schreiner RP. 2016. Nutrient uptake and distribution in young Pinot noir grapevines over two seasons. Am J Enol Vitic 67:436-448