The brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB), Halyomorpha halys, has caused significant yield losses in fruit and nut crops around the world. Its appearance in California around fifteen years ago was no surprise after it had already invaded large portions of the country, especially the mid-Atlantic states. Here, we give background information and an overview of the brown marmorated stink bug biology, its current status within California and its potential to impact pistachio production.

Invasion History of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug

Originally, BMSB was known only in China, Korea, and Japan. With increasing global trade and transport, it started, like many other species, spreading to new parts of the world. Outside of its native range, it was first identified from samples in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 2001, but the earliest confirmed sighting of the invasive stink bug already occurred five years prior. That invasive species are present for years before their official recognition is common since they generally arrive in low numbers and have to build up their populations before they can cause any damage—which then generally attracts attention and alarm.

In the case of the brown marmorated stink bug, regular interceptions, for example, in the UK and New Zealand show that it probably traveled in transport crates or shipping containers to the US, and later to Europe, Canada and Chile. Shipping containers provide BMSB adults (the overwintering stage) with shelter and protection. Other favored overwintering sites are other human-made structures, including homes, garages, barns, etc. This, in combination with their likely arrival at trade hubs such as large cities, and their tendency to form overwintering aggregations that can consist of hundreds or even thousands, has led to them being classified as a ‘nuisance pest’. Indeed, unlucky homeowners have struggled with up to 25,000 BMSB hiding in their walls, attics, and other living spaces during the winter. Of concern for farmers in California is BMSB movement from urban shelters into agricultural crops.

Biology of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug

The brown marmorated stink bug biology is similar to many of our native stink bugs and shares many traits with leaffooted bugs and smaller ‘true bugs’. They have an egg, nymph, and adult stage. Adult BMSB are about half an inch long, with a brown body and white striped antennae and legs.

In California, they can be confused with Euschistus species or the predatory Rough-shouldered stink bug Brochymena; the website www.StopBMSB.org has a helpful compendium with pictures and detailed descriptions. After mating, adult female BMSB lays up to ten egg masses, often consisting of about 28 lightly blue-green colored eggs, over the span of her life, which can last several months. The nymphs undergo five instars until they reach the adult stage. The red-brown and black first instar nymphs can be seen sitting around the egg mass after hatching, feeding on the symbiotic microorganisms that will make it possible to digest their various host plants. After that, they start wandering off in search of food. Second to fifth instar nymphs are black and white in appearance and can walk rather long distances for their small size, for example fifth instars can walk 65 ft within only four hours.

Both the nymphs and the adults feed by inserting their needle-like mouthparts into a variety of plant tissues including stems, leaves, and especially reproductive structures, secreting digestive enzymes and sucking up the liquified plant material. The mechanical damage and specifically the chemical changes due to the excreted enzymes can lead to discoloration, deformation and the abortion of fruiting structures, all of which make the crop unmarketable. Many stink bug species are known mainly as secondary pests in various crops. Often, an individual species has different host plants to fulfill their nutrient requirements and can therefore behave as a pest in different crops or take refuge in a naturally occurring host.

The brown marmorated stink bug has more known host plants than other stink bugs; in the US alone, more than 170 plant species have been reported, many of them economically important crops. These include vegetables, leguminous crops, fruits, nuts, and ornamentals. In the first big outbreak year, 2010, damage caused by BMSB to apple production of the mid-Atlantic states led to economic losses of $37 million. Other examples, from Georgia and Russia, include the destruction of the hazelnut crop, which is highly important for these regions, to such an extent that the government paid citizens for every bucket full of stink bugs. In contrast to those stories, BMSB crop damage has been relatively quiet in California and the rest of the West Coast.

The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug in California

Not long after the brown marmorated stink bug was reported on the East Coast, in 2002, the first individual was discovered in a storage unit in California. Like most invasive species, there can be years between the first interceptions of individuals and the establishment of a reproducing population. Consequently, the first established brown marmorated stink bug populations in California were not reported until 2006 in the Los Angeles area and 2013 in Sacramento. The following year, 2014, monitoring efforts were put into place and, since then, the invasive stink bug has been shown to be established, or at least been detected, in most California counties (https://cisr.ucr.edu/invasive-species/brown-marmorated-stink-bug). However, presence and abundance are two separate matters. The warm climate allows the invasive insect to complete two generations per year and BMSB damage has been reported in several almond orchards near Modesto, Calif. The stink bugs have also been sighted in commercial peaches, but most sightings still occur in urban centers rather than agricultural areas, often associated with the common ornamental tree, the tree of heaven (which is also from Asia). Good news is that in many monitoring sites, trap catches have actually been decreasing for several years. The current situation therefore sees BMSB spreading in California, but at a low density apart from localized larger populations. The bad news is that, in addition to almonds, many California specialty crops are either known or potential hosts.

Damage Potential in Pistachios

To assess the threat of the brown marmorated stink bug to California’s pistachio production, we conducted trials under Central Valley conditions by caging terminal branch endings with pistachio clusters were caged, just after bud-break, and exposing the developing nuts to BMSB for a five-day feeding period. Trials were conducted throughout the season to account for hardening of the pistachio shell and changing temperatures. As a comparison, clusters were also exposed to adults of two native species that feed on pistachios, the flat green stink bug Chinavia hilaris and a leaffooted bug, Leptoglossus zonatus.

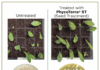

Native true bugs common in pistachios can be grouped by their size: ‘small bugs’ like mirids are more abundant early in the season and cannot pierce the pistachio shell later in the season, while ‘large bugs’ like stink bugs and leaffooted bugs continue to cause damage during mid- and late-season. The insertion of their needle-like mouthparts and the secretion of digestive enzymes can result in external damage, brown to black lesions of the outer fruit layer, the ‘epicarp lesions’ that can stain the outer shell and lower market value. Especially after mid- to late-season feeding, epicarp lesions often appear with a delay or not at all, hiding the internal damage: if the insect’s mouthparts reach the endosperm tissue, it can become necrotic or lead to aborted nuts. Along with direct damage, the feeding can lead to fungal infections, ‘stigmatomycosis’, that result in blackened, foul-smelling kernels.

We found that, one to two weeks after feeding, BMSB caused similar amounts of external nut damage (i.e., epicarp lesions) as did the native species tested. However, by following clusters development and damage throughout the season, we noticed more epicarp lesions formed later in the season in the BMSB exposed cages. Shortly before harvest in September, there were significantly more damaged nuts per cluster (based on epicarp lesions) in BMSB cages than in the green stink bug or leaffooted bug cages, independent of when the feeding occurred during the season. This indicates that adults of the brown marmorated stink bug can cause more external damage than our native large bug pests. However, the more important internal damage criteria such as the number of necrotic kernels, aborted nuts or kernels with stigmatomycosis were not different between these large bug pest species tested.

The brown marmorated stink bug may generally cause more crop damage than other large bugs because of their feeding behavior or saliva composition – this is still being investigated, but the main factor that makes them such an important pest are the sheer numbers in which they occur in affected areas, such as Virginia. In California’s Central Valley, this is generally not the case, at least at this time. One potential explanation for this phenomenon are the hot and dry summers in the Central Valley, as well as the large-structured agriculture, with thousands of contiguous acres of commercial agriculture, that may make it difficult for BMSB nymphs to switch host plants to access all their required nutrients.

To point this out, in another trial we caged first instar BMSB nymphs on different California specialty crops throughout the last two seasons and showed high nymphal mortality. This could explain the low overall abundance of BMSB in the Central Valley—it’s just too hot and dry. They were generally more likely to reach the adult stage on almond than on pistachio, which could be explained by the close relation of almond to one of their favorite host plants, peach. This is also in line with the records of brown marmorated stink bugs in California almonds, but so far not in pistachio. Still, even on almond survivorship was low.

To conclude, the brown marmorated stink bug has the potential to cause at least as much damage in pistachios as our native stink bug and leaffooted bug species. This is, however, dependent on its abundance in the respective areas, which is currently low.

What You Can Do if You Suspect You Have Brown Marmorated Stink Bugs

In case BMSB becomes a bigger issue in California, there are a number of measures that can be taken. The first line of defense is monitoring. Take into account that border rows are generally more affected than the inside, especially if the orchard or field is close to woodlands or preferred host plants, like the tree of heaven. Common sampling programs include sweep and beat samples as well as visual counts, but those methods have not proven to be as reliable as pheromone traps. There are many different trap types available of which the most effective one is the black pyramid trap, and the most economic one a clear sticky trap that can be mounted on a pole. The lure most commonly used is a blend of the aggregation pheromone of BMSB and the closely related oriental stink bug (Plautia stali).

Trap counts can be used to determine insecticide applications as opposed to calendar-based applications, but the system is still being optimized because it is more difficult to relate trap catches with BMSB densities in the orchard than it is for other pests. Pheromones and insecticides can also be combined in ‘attract and kill’ methods using for example ‘bait trees’ that are equipped with pheromone lures and are sprayed in regular intervals. This can ideally reduce pest populations with only a small area affected by the insecticides, thereby protecting natural enemies, decreasing the risk of secondary pest resurgence, and reducing costs. Research efforts to make these systems commercially available are currently underway on the east coast.

When the brown marmorated stink bug first started threatening yields in the mid-Atlantic states, growers applied insecticides registered for native stink bugs such as pyrethroids and neonicotinoids, which unfortunately failed to provide complete control of this invasive species. Part of the failure was due to the combination of a very mobile insect and products with a short residual activity. It is also easier to kill the overwintering adults than the subsequent generations, so once population densities are high during the season, application efficacy is reduced.

One reason to back off of pesticide treatments for low densities of BMSB are its natural enemies. Many predators are feeding on different life stages of this bug, although the levels of control in California are still not clearly known. There are a number of native parasitic wasps that attack the egg stage of stink bugs, including this invasive stink bug. However, since the brown marmorated stink bug is a novel host for them, they have yet to adapt to it; often, their offspring are not able to develop within the eggs of the brown marmorated stink bug. Currently, BMSB control in the United States by resident natural enemies is not sufficient to reduce population sizes significantly and prevent crop losses. There is, however, a parasitic wasp that could make a difference: Trissolcus japonicus, also known as ‘the samurai wasp’.

eggs of the brown marmorated stink bug. (Photo courtesy of Warren H. L. Wong)

The Samurai Wasp

To the naked eye, the samurai wasp looks just like any other of our native egg parasitoids that attack stink bugs: it is smaller than a grain of sand, mostly black, and completely harmless. But unlike its relatives, it has the same area of origin as BMSB and is very well-adapted to this host. In Asia, the samurai wasp is the most important natural enemy keeping the brown marmorated stink bug in check. Like its host, it has made its way to North America and Europe. After first being discovered in the eastern part of the US in 2014, it spread, presumably with multiple new introductions from Asia, to the West, and has recently been recovered in the Los Angeles area. Across the country, release and redistribution efforts are underway and a national consortium of researchers is working on the development of an optimal strategy to use the samurai wasp to control BMSB. The samurai wasp is unlikely to be a silver bullet but will be one of many factors helping with the suppression and sustainable management of this invasive pest.

In California, most growers have so far been luckier than their colleagues on the east, and there are no indications that that will change soon; but the brown marmorated stink bug has been full of surprises and considering that it has the potential to severely impact SJV nut production, everyone should continue to be calm but vigilant.

For a list of references please email judithmstahl@berkeley.edu.