By: Thomas A. Turini, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Vegetable

Tomato spotted wilt virus is a thrips-transmitted virus that can infect many crops and weeds. In California’s Central Valley, in an important processing tomato production area, this virus disease may cause substantial economic damage. The most recognizable symptoms include fruit with oval protruding oval deformities or irregular concentric ring color patterns and this virus can kill shoots and plants, so both quality and yield are affected. The host range of this virus includes many common crops and weeds and likely survives the winter on a few weed or crop plants, but quickly amplifies on tomatoes in spring. Therefore, risk increases during the season. The virus is transmitted by thrips; primarily Western Flower Thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis in the Central San Joaquin Valley. The vector must feed on an infected plant as a nymph to be capable of transmitting the virus as an adult. Risk of loss due to TSWV can be reduced but management in high risk situations is going to depend upon several tactics. Resistance to the virus is available in both fresh market and processing tomato varieties; however, in some production areas, resistance-breaking TSWV has been reported and is likely to develop in regions where the gene is heavily relied upon. A few foliar insecticides have been shown to bring down thrips population densities and reduce incidence of TSWV symptomatic plants, but will not keep the virus down to commercially acceptable levels under high disease pressure. Under situations where there is a history of the virus, identify risk factors, which may include weed or crop sources of the virus in early spring, ensure that transplants are not arriving with infection, consider variety susceptibility, plant date, thrips management programs to calculate your risk of experiencing damage. Once there is an appreciation for your risk factors, you have capacity to mitigate disease risk by modifying any of these components that contribute to a situation in which this disease causes economic damage.

Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) was present at low levels and was largely regarded as a curiosity 15 years ago, but by 2005, this severity and incidence of this virus increased to levels that caused severe economic damage in the Central San Joaquin Valley. In response the California Tomato Research Institute funded a comprehensive research project to better understand and control this viral disease.

Identification is critical to implementation of an effective program because management of TSWV requires different tactics than other diseases. This virus disease is associated with several striking symptoms, but also has symptoms that can be confused with other virus diseases or even diseases caused by very different pathogens. Symptoms of TSWV vary by stage of crop development when infection occurs and by other factors. The most recognizable symptoms of TSWV in tomato include fruit with protruding oval deformities or irregular concentric ring color patterns. Plants infected shortly after transplant will produce foliage with dead spots or have more superficial patterns on the upper leaf surface giving a bronzing appearance and the entire plant will die before producing fruit. When fruit are forming at the time that infection occurs, fruit will be deformed and discolored, foliage will show bronzing symptoms and dieback. Plants infected at late stages of development will have symptoms limited to shoots. There are quick tests that are easily performed in the field or office available for purchase from AgDia at www.agdia.com or EnviroLogix at www.envirologix.com.

An awareness of virus and vector characteristics is helpful in considering control program components. The virus has a wide host range that includes sow thistle, prickly lettuce, mustard, London rocket, malva, Russian thistle and many others. Crops that also may be infected includes beans, eggplant, lettuce, pepper, potato, and spinach. The virus does not survive outside of a living host, so it is likely to be surviving in winter weed or crop hosts while there are no tomatoes in the area. In central California the primary vector is Western flower thrips (WFT), Frankliniella occidentalis. The thrips must acquire TSWV by feeding on an infected plant as a nymph, pupate in the soil in the case of WFT, and emerge as an adult capable of transmitting the virus. The thrips may survive for more than 45 days and is capable of transmitting the virus. During most years, thrips movement is very low from November through January, and the levels observed in weeds and crops in January and February are very low, so all indications are that after winter, this virus is present in very low levels in the environment. In March and early-April, there are low levels of TSWV present in the processing tomato production areas, but the virus quickly amplifies on the large and concentrated areas of tomatoes so that by June, the virus is present at much higher levels and risk of economic damage due to TSWV is much higher than early in the season.

In addition to crop and weed sources, recent research suggests that adult thrips with TSWV emerging from pupae in the soil are another potential source of early season TSWV inoculum. In this case, the immature thrips that fed on an infected plant prior to pupating in the fall harbor the virus through the winter. As soil temperatures increase in spring, the infectious adults may emerge and serve as a source of the virus early in the season.

Varieties resistant to TSWV are available for both processing and fresh market production. Commercial varieties with resistance are using a single gene resistance, Sw5. With repeated and widespread use of single gene resistance, virus strains with capacity to reproduce within resistant plants will be selected for. In the event that a strain or strains with resistance breaking capacity is present in the population, selection for an increase of that strain or strains will occur in the presence of dense use of this single gene resistance. Therefore, while plant resistance is a critical tool in managing TSWV, exclusive reliance on this tactic should be avoided. In addition, careful attention to any evidence of the presence of plant resistant strains is critical. If typical fruit and foliar TSWV symptoms are present on more than 3% of the plants that have Sw5 resistance, there may be resistance breaking strains present.

Some susceptible varieties are more susceptible than others. In the absence of genetic resistance, differences in TSWV expression were documented in susceptible varieties. In studies conducted at the University of California West Side Research and Extension Center (UC WSREC), 10 to 16 varieties were compared in 13 trials conducted from 2007 to 2012. Based on TSWV incidence in susceptible varieties, entries were placed into three categories (Table 1). It is notable that there are factors aside from variety that influence performance of these varieties.

Insecticide use to control thrips can be challenging, but use of some foliar insecticides reduced TSWV incidence in studies conducted at UC WSREC. Thrips concentrate in flowers or other protected location, have tremendous reproductive potential and may develop resistance to insecticides; however, as a component of a management program, they may be useful in reducing economic impact due to TSWV.

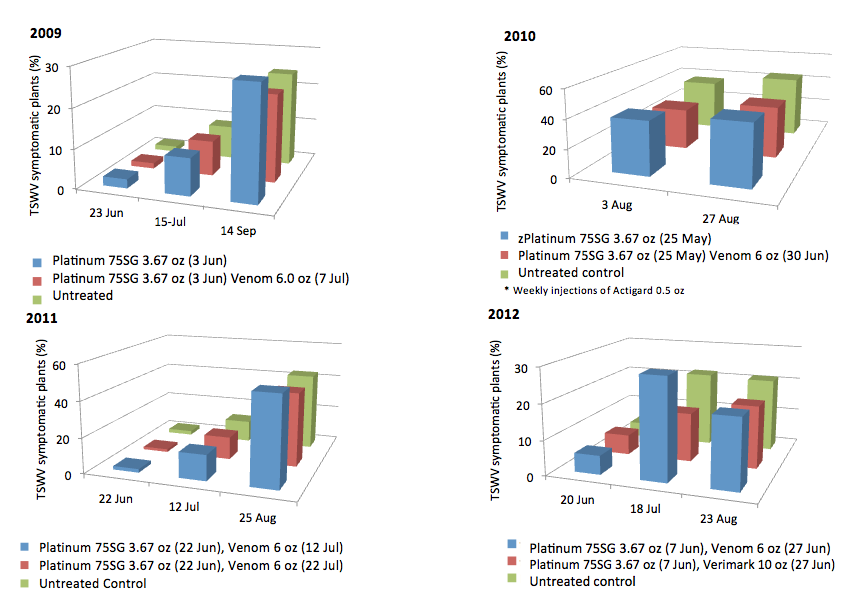

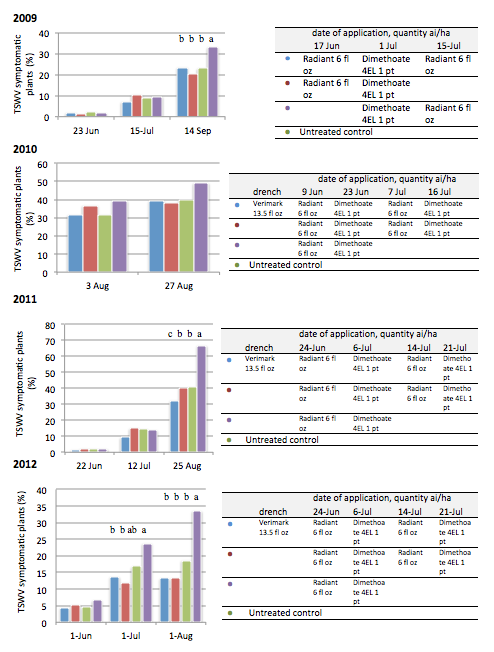

In foliar insecticide efficacy comparisons experiments conducted from 2007-2012 the only insecticides that consistently reduced WFT densities were Radiant, dimethoate and Lannate (data not shown). Insecticide program evaluations conducted at UC WSREC included drip injected materials as well as transplant drenches and foliar applications as detailed in Figures 1 and 2. Under the conditions of comparisons of program studies over five years, drip injected materials were ineffective, but foliar applications were generally helpful in reducing TSWV disease incidence. No significant differences were documented with drip injected materials (Fig 1 and 3) while foliar programs reduced TSWV incidence in 2009, 2011 and 2012 (Figure 2). In 2010, no significant differences were observed between any treatments (foliar, drench or control) (Figure 2). In 2010, Performance of Verimark as a transplant drench was inconsistent. In comparison to the program lacking the Verimark application, the Verimark transplant drench reduced TSWV symptom incidence in 2011, but not in 2010 and 2012 (Figure 2) ). In 2010, regardless of the treatment, there were no differences between treatments and the untreated control, which was likely due to very high population densities of thrips from an infected tomato field near the experiment. This highlights the limitations of what can be accomplished with insecticide treatments and that without other strategies also implemented, the likely failure to provide commercially acceptable levels of control under high disease pressure. The insecticide treatments are effective largely in that they reduce secondary spread, or spread of the virus within the field, to prevent spread from external sources of infective thrips is unlikely with infield applications.

Rogueing, which is removal of TSWV symptomatic plants, may be effective and even economical under some circumstances. However, if substantial external sources of infective thrips are contributing to the disease increase or there are already substantial levels of TSWV infected plants in the field, this is not likely to be effective. Also, it may be difficult to economically justify this approach depending upon the market for the tomatoes or the value of labor.

Integrated Pest Management can be applied specifically to TSWV for the greatest sustainable levels of success under high pressure situations. Careful inspection of the area for potential sources of inoculum and avoiding planting crops near sources, to prudent selection of varieties to starting with virus-free transplants are important pre-plant steps. Following planting, continue to monitor not only your field but fields in the vicinity for TSWV symptoms. At the first detection of the virus in the area or in the field, begin treatments with insecticides. Generally, few applications will be needed and under the conditions of the studies in Central California, two applications were as effective as more treatments. After harvest of tomatoes or any crop, quick and complete removal of the crop and weeds are critical and weed control throughout the year in the production area can reduce pressure.