Mechanization progress in a traditionally labor intensive crop is yielding improved production and quality.

Wine grape growers in California’s San Joaquin Valley and other wine grape growing regions are finding benefits in University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE) research into mechanized dormant pruning and shoot removal. While the traditional winegrape training system can work for mechanical harvest, mechanical dormant pruning and shoot removal operations have not been as successful. The aim in further mechanization is to lower labor costs while still ensuring crop yields and quality.

Mechanical Pruning

University of California (UC) researchers Kaan Kurtural, a specialist at the UC Davis Department of Viticulture and Enology and George Zhuang, UCCE viticulture advisor in Fresno County found that introducing mechanized pruning and other vine management operations could be done in existing vineyards. Vines could be re-trained during the transition from hand pruning and they would still retain production and fruit quality.

This choice is significant for wine grape growers in the San Joaquin Valley, who produce more than half of the wine grapes in California, because in recent years they have faced increased labor costs, worker shortages and tighter profit margins.

A report from UC Davis noted mechanical pruning in wine grape vineyards reduced labor costs by 90 percent, increased grape yields and had no impact on the berry’s anthocyanin content.

One of the research sites was an eight-acre portion of a 53-acre block of 20-year-old Merlot vines in Madera County. The field study took place over three growing seasons.

The report noted that following completion of the research trial, the remainder of the vineyard was converted to the single high-wire sprawling system used in the trial block. UC researchers also reported other wine grape growers in the area are beginning to transition vineyards to the new system.

Trellis Systems

In the San Joaquin Valley, the traditional trellis system consists of vines head trained to a 38-inch tall trunk above the vineyard floor and two eight-node canes laid on a catch wire in opposite directions. There are also two eight-node canes attached to a 66-inch catch wire. This system can work for mechanical harvesting, but not dormant pruning and shoot removal and limits options for other canopy management operations.

In the trial, the vines were converted to a bilateral cordon-trained spur pruned California sprawl training system or to a bilateral cordon-trained, mechanically box pruned single high wire sprawling system. The UCCE report noted that the second system was the most successful for mechanical pruning.

A report on converting vineyards to mechanical pruning, authored by Kurtural, Andrew E. Beebe, Johann Martinez-Luscher, Zhuang, Karl T. Lund, Glenn McGourty and Larry J. Bettiga and published in HortTechnology, concluded that conversion of traditional systems to the bilateral cordon-trained mechanically box pruned single high wire sprawling system (SHMP) sustained greater yield with more clusters per vine and smaller berries without affecting the canopy microclimate.

This was due to a higher number of nodes retained after dormant pruning. Compared to the traditional and the bilateral cordon-trained spur pruned California sprawl training system, the SHMP canopies filled their allotted space earlier. The report authors said that earlier canopy growth coupled with sufficient reproductive compensating responses allowed for increased yields while reaching maturity without a decline in anthocyanin content. This system is recommended for growers in the hot Central Valley winegrape growing areas to increase sustainability of production while not sacrificing adequate berry composition.

From 2013 to 2015, labor costs per acre with the SHMP system totaled $463.05 while the hand labor during that time totaled $1,348 per acre.

Vineyard Mechanization Conversion

Kurtural also led research on vineyard mechanization conversion in a 40-acre vineyard in Napa County. The research began as a labor-saving trial, but Kurtural reported that when they began looking at the physiological aspects of how plants grow, there were benefits to fruit quality as well.

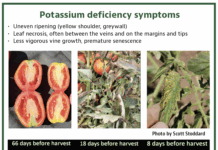

Taller canopies due to increased trunk height protect the developing winegrapes from sun damage. The taller canopies and the increased yields from mechanically pruned vines also mean that water and nutrient requirements in the vineyard can be different from those in hand-pruned vineyards.

Zhuang confirmed that interest in mechanical pruning and vineyard transition is growing, not only in the San Joaquin Valley, but on the Central Coast where sufficient labor for cultural practices is becoming difficult to find. The premium wine grape growing areas in northern California have strong traditions with hand spur pruning, but tighter labor markets may lead growers there to consider mechanization.

The vine re-training could also be feasible for raisin grape vineyards, Zhuang said, but not for table grapes due to different production needs.

Changes in Nutrient and Irrigation Management

Where mechanized pruning is done, Zhuang said, there would need to be changes in nutrient management and irrigation. Water and fertilizer requirements for mechanically pruned vines are different than those of hand pruned vines.

“Canopies will grow faster and bigger on those vines,” he said.

Mechanized pruning operations will leave many more buds, as many as double the number left after spur pruning, and that will change the plant physiology. Buds will break earlier in the growing season, Zhuang said and the vines would begin to push new growth much faster. The early growth will mean early water demands will need to be met. Demand for nutrients will be accelerated by the early growth, larger canopies and yields.

Labor

Nick Davis, ranch manager for The Wine Group, a company that farms 13,000 acres of wine grapes between Kern County and Lodi, said reducing the impacts of increased labor costs prompted the decision to move toward mechanized pruning in their vineyards.

Any new vineyard developed by the company, in the Central Valley, will be set up for mechanization, Davis said, and the goal is to become 100 percent mechanized in the future.

“We know this system works, but we will be working on managing the hedge-pruned box and not allow it to creep out,” Davis said.

Transitioning existing vineyards requires removal of cross arms and foliage wires and t-posts, but if the berry quality and the production are the same or better than vines that are hand pruned, transitioning will continue, Davis said.